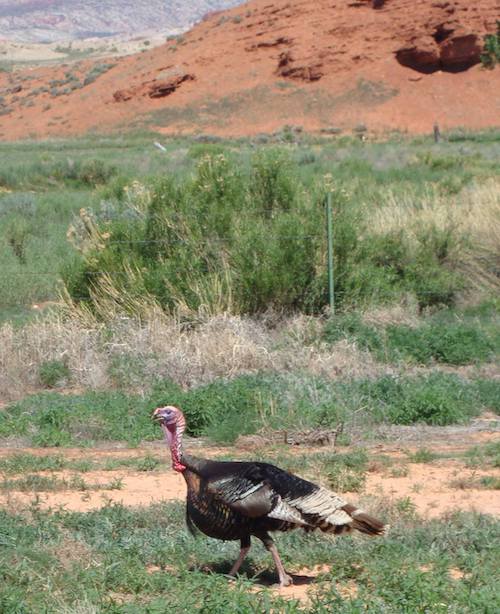

The wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is often misaligned by city dwellers as a dumb bird, suitable only for the Thanksgiving table. Those of us who are closer in touch with our wild roots, however, know this large colorful thunder chicken as a crafty, wary, and magnificent creature of the forest.

Weighing between 12-25 pounds for the male (tom) and 6-12 pounds for the female (hen), the wild turkey is covered with dark feathers that have a bronze-green iridescence. The wings and tail feathers are tipped with white or light brown bars.

Like the domestic turkey, the wild turkey has no feathers on its head. The bare skin on the head and neck varies in color from blue to gray to red. A distinguishing anatomical mark on the turkey’s forehead is the snood, a fleshy flap that is white when the bird is relaxed but will become red and elongated during courtship.

A prominent feature on the tom, and some hens, is the beard protruding from its chest. This beard is made of modified feathers and looks like a group of long, black bristles hanging from the breast plumage. The beards start growing when the bird is five months old and will grow up to five inches every year.

The wild turkey has between 5,000 to 6,000 feathers, and nearly all of them come into play when it executes its signature move, the strut. When strutting for mating or dominance, the male will fan out all 18 tail feathers and puff up the body feathers to showcase its power and plumage. The turkey will bring its head and neck into an “S” shape, and the snood will elongate as it’s filled with blood.

The strutting turkey will also take a few short steps and issue a sharp huff sound followed by a drumming sound.

Males will sometimes strut outside the breeding season in an attempt to get the mating game started early.

Hens may also strut to show dominance or in response to a predator threatening her chicks.

There are five recognized subspecies of wild turkey found throughout every state in the U.S., excluding Alaska. The eastern subspecies inhabit the eastern and central states. The Merriam’s, Rio Grande, and Gould’s are found in the western U.S. and have whiter feather markings and shorter legs than the eastern populations. The Osceola subspecies occurs only in southern and central Florida.

Turkey fossils have been discovered in the southern U.S. dating back more than five million years ago and have a rich history with the continent’s early settlers.

The bird and its eggs were a favorite meal of Native American tribes. Feathers were used for arrow fletching, and many leaders used turkey feathers as part of their headdresses.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the wild turkey’s population was severely reduced due to hunting pressure and habitat loss. Estimates in the late 1930s put the native turkey population at 30,000.

Fortunately, conservation efforts have helped to reintroduce this majestic bird to most of its former range. Today, approximately seven million wild turkeys roam the U.S.

Wild turkeys spend most of their time in gender-centric flocks, preferring to live in and around mature forests, particularly those with nuts and located near fields. Hens will live with their female offspring and often combine flocks. Female flocks can often number 50 or more birds with some winter flocks consisting of nearly 200 birds.

Toms form their own flocks, segregated by age. The older males stick together, and the younger males (jakes) will create their individual subgroups.

The flock will generally move about two miles in one day, depending on the location of available food and water resources. Annually, the flock’s home range will be between 350 to 1,300 acres.

Within the flock, turkeys are always communicating with each other. Their vocabulary has 28 distinct calls, ranging from mundane poultry conversations to the tom’s iconic mating gobble.

When feeding, hens will communicate with one another through a series of soft calls when they’re scratching the ground in search of nuts, berries, and insects. If disturbed or frightened, the flock scatters in multiple directions to confuse the potential threat. Once the area is deemed safe, the hens start calling with a loud yelp to reassemble the flock.

The wild turkey has outstanding eyesight. The birds have a 270-degree field of vision and can see in color. Their daytime vision is three times better than a human’s, but their night vision sucks.

When night falls, the turkey becomes extremely vulnerable to predation from coyotes, foxes, and bobcats. That’s when the birds take to the trees for safety and roost for the night. The wild turkey will usually roost in the same large trees on the highest branch that will support its weight.

In mid-March, the males turn up the volume on the turkey strut to do their sexy best to attract hens. Hens evaluate the tom’s suitability based on his strut, healthy appearance, and possibly, beard length. When she’s ready, she’ll crouch down to signal it’s time for mating.

After the breeding period ends, the hen will start searching for shallow depressions on the ground as potential nesting sites. She will lay 10-12 eggs over two weeks with incubation starting once the last egg is laid.

Over the next 26-28 days, the hen will only leave the nest for short periods to feed. Otherwise, she can stay on the nest for several consecutive days, moving about once an hour to turn and reposition the eggs.

As the eggs start to hatch, the hen makes soft clucks to imprint the chicks. Within 24 hours, the chicks are able to follow her away from the nest

By their second week, the young turkeys (poults) can fly short distances and can roost by their third week.

The poults will be full-grown by winter, and if they don’t fall to predation or disease, they can expect to live up to four years in the wild.