An icon of the American Old West, the tumbleweed is actually a non-native species of Russian thistle (Salsola tragus) that is suspected of entering South Dakota with Ukrainian farmers and their flax seeds in the early 1870s. The plant is now considered a noxious weed that has spread across arid regions throughout North America.

When the plant dies, it breaks off at the stem and is carried away by the wind. As the dead plant rolls across the ground, it disperses nearly 250,000 seeds across the arid soil. This same rolling dispersal mechanism is actually used by 10 plant groups that fall under the broad umbrella of the tumbleweed name.

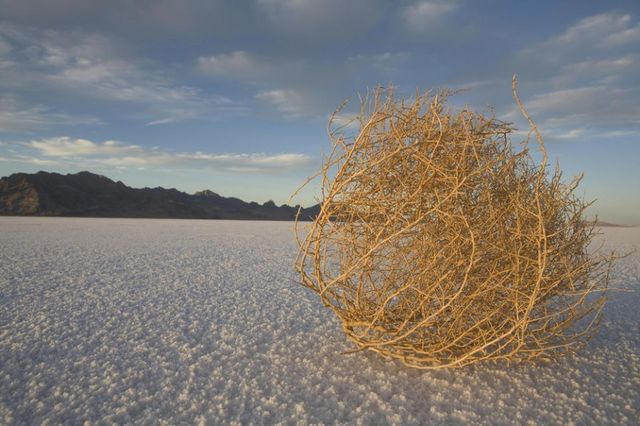

When alive, the Russian thistle resembles the skeleton of a shrub. It ranges in size from six inches to over six feet in diameter. The plant thrives in salty and alkaline soils but can be found in a wide elevation range from below sea level (Death Valley) to 8,500 feet. The tumbleweed can be seen in abandoned agricultural fields, vacant lots, roadsides — anywhere there is no grass which out-competes the Russian thistle.

The tumbleweed’s tangled history took center stage when prairie grasses were removed for agriculture in the late 1800s. The Russian thistle quickly took advantage of the smooth, flat environment that was perfect for its wagon wheel styled seed dispersion routine. By 1890, the plant had spread from South Dakota to a dozen states and tumbled its way to the Pacific Coast within another 10 years.

The Russian thistle’s green flowers and red- or purple-striped young stems are a common food source for mice, Prairie Dogs, Pronghorn, and Bighorn Sheep.

Unlike other most other seeds, the tumbleweed’s seed does not have a protective coating or internal food reserve. Instead, each seed is an embryonic plant covered with a thin membrane. The seed lays dormant until rain causes the seed to germinate, which can happen anywhere between 28 and 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

The Russian thistle will reach its mature size in the fall and begin to die in the winter. Specialized cells in the plant’s stem allow it to easily separate from its roots when hit by a strong gust of wind, sending the tumbleweed, and its seeds, rolling across the landscape.

In higher winds, tumbleweeds can become entangled with one another and collect to block roads, enclose homes and even overwhelm entire neighborhoods. The tumbleweed is essentially highly mobile kindling and is considered an extreme fire hazard.

In something out of a B Grade Monster movie, on April 2018, 60 m.p.h. winds pushed tumbleweeds into a Victorville, California neighborhood, blocking the entrances to nearly 100 homes and piling up high enough to reach the second story of several homes.