The orca (Orcinus orca), also known as a killer whale, is the largest member of the dolphin family and the ocean’s apex predator.

With its distinct black and white markings, the orca is one of the more widely distributed sea mammals and is found in every ocean in the world. The global population is around 50,000 whales, with approximately 2,500 living in the eastern portions of the North Pacific Ocean.

An adult orca can grow up to 32 feet in length and tip the scales at 11 tons. The animal’s cylindrical shape with a taper at each end contributes to its underwater hydrodynamics, allowing it to reach speeds exceeding 30 knots (about 35 mph).

The orca has a black top, white underside, and white patches near its eyes. Males have larger tail flukes, dorsal fins, and pectoral flippers than females. Both males and females have a white or gray patch behind their dorsal fin that varies in size and shape. These patches, also called saddles, are unique to each orca and are often used to identify individuals.

Orcas live and hunt in social groups, which accounts for the nickname the “sea wolves.” These groups, or pods, are usually maternally related and range in size from three to 50 whales.

The orca relies on a series of clicks, pulsed calls, and whistles to communicate and navigate. Each pod uses a unique set of calls learned and transmitted among the members. Some of the pod’s “cultural knowledge” passed down through vocalization includes what food to eat, where to find it, what to avoid, and how to hunt various species.

Each pod has a distinct “accent” that orcas use to distinguish between pods just through sound.

Orcas can also learn new “dialects,” even across species. Three orcas housed near bottlenose dolphins for three years changed their vocalizations to match those of the dolphins more closely, including the dolphins’ clicks and whistles.

A 17-year-old female orca named Wikie, living in the Marineland Aquarium in Antibes, France, has even learned to mimic human speech by saying “hello” and “goodbye.” She communicates with her head above the water and can even blow raspberries, mimic a creaky door, and repeat numbers.

While the orca’s diet ranges from penguins to great white sharks and blue whales, the pod’s behavior and learned hunting tactics are the primary determinants of food selection. For example, one pod in the Pacific Northwest concentrates on salmon. At the same time, another in the same area pursues seals and squid.

An orca’s hunting tactic varies with each prey. Underwater prey is found using echolocation. The orca will create sounds that bounce off fish, juvenile whales, and other large marine animals.

Once the prey is found, orcas will implement various tactics during the hunt. Groups of fish are herded before being stunned with tail strikes. Orcas will also coordinate attacks against seals seeking refuge on ice by creating waves to knock the animal off the ice and into the water.

If the seal is sunbathing on a warm beach and close to the water, killer whales will launch themselves onto the shoreline to grab the seal and drag it out to deeper waters.

An orca’s tooth is about three inches long, one inch in diameter, and is used to tear apart prey, not chew it. There are usually 10-14 teeth on each side of the jaw, totaling 40-56 teeth.

In March 2019, a whale researcher and his students witnessed a pod of 20 orcas attack and kill a 70-foot blue whale off the west coast of Australia. The orcas worked together to exhaust the whale, biting chunks of flesh throughout the three-hour attack.

As the blue whale weakened, two orcas jumped on top of the whale and forced it under the water until it drowned.

Like other predators, orcas have a “preferred cut” on their prey. On this particular blue whale, the tongue was the first piece consumed. With great white sharks, orcas seem to eat the shark’s liver and nothing else.

These differing diets and other recognizable physical variations and behaviors have led scientists to classify orca ecotypes within the same species. There are 10 distinct ecotypes, with five living in the Northern Hemisphere and five in the Southern Hemisphere.

A female orca will reach sexual maturity between 10 and 13 years old. There is no calving season, so births take place throughout the year. An orca’s gestation period is about 17 months, with a single, 400-lb calf born. The calf will nurse for one year and remain near its mother for two years. A male orca will stay with its mother for life.

Research has revealed that a female orca can give birth every year for up to 25 years. Orcas, beluga whales, narwhals, and humans, are the only known species to undergo menopause.

The average lifespan for male orcas is 30 years, with some individuals living up to 60 years. Most females live for 50 years, with a few making it to over 90 years old.

Like dolphins and whales, orcas breathe through a single blowhole on top of their head. Covered by a muscular flap, the blowhole is relaxed in the closed position to create a watertight seal. The muscular flap contracts to open. While orcas can hold their breath for up to 15 minutes and dive to 300 feet, they usually surface about once every minute when moving quickly and once every 3-5 minutes when cruising.

Unlike land mammals, orcas do not have a breathing reflex that allows them to breathe while sleeping or unconscious. The orca has to actively decide when to breathe. This is why only one half of an orca’s brain sleeps while the other stays awake, alert, and controls breathing. When the right half of the brain is sleeping, the orca’s left eye is closed. And vice versa. During their alternating sleep period, orcas will swim slowly close to the surface.

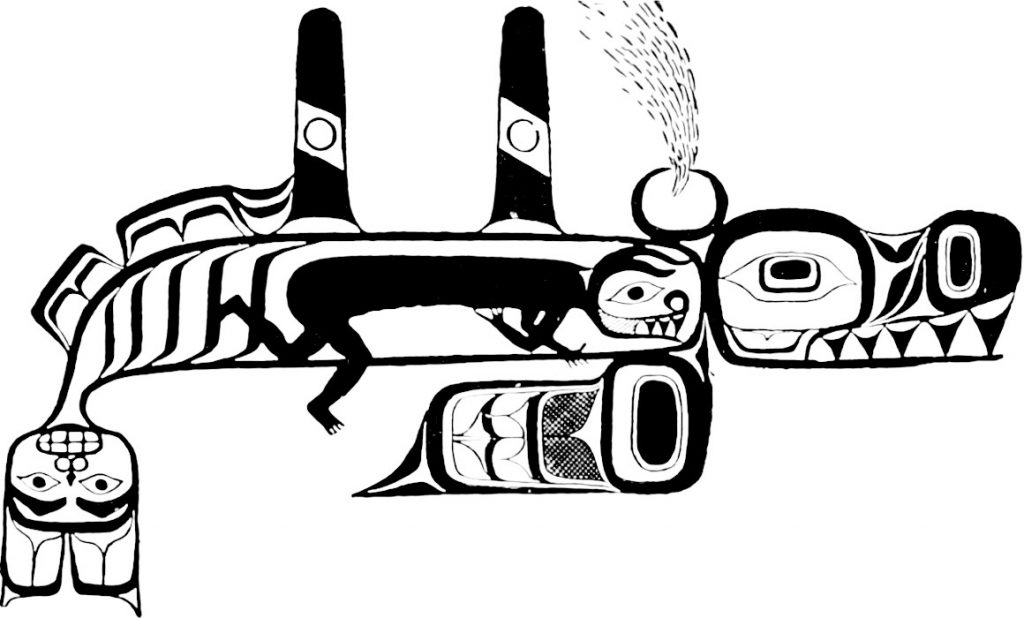

Orcas are featured throughout the history, art, and religion of the Pacific Northwest coastal indigenous peoples. According to the Haida People of British Columbia, orcas are the most powerful ocean animals, and they live in undersea houses and villages. Once the orcas were submerged, they transformed into human form. Tribal members who drowned were thought to live with the orca.

Today, all orcas are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The Southern Resident Distinct Population Segment, which ranges from central California to southeast Alaska, is the only endangered killer whale population in the U.S.