The twisted trunk of the manzanita tree, with its smooth, cinnamon-red bark, has become a scenic fixture in the landscapes of the American West. Found on dry, sunny slopes at low elevations, the manzanita is an evergreen that is treasured for the beauty and sustenance it provides.

While there were only three original native manzanita species, today, approximately 106 known species (genus Arctostaphylos) inhabit arid climates throughout Arizona, Nevada, California, Oregon, and Washington.

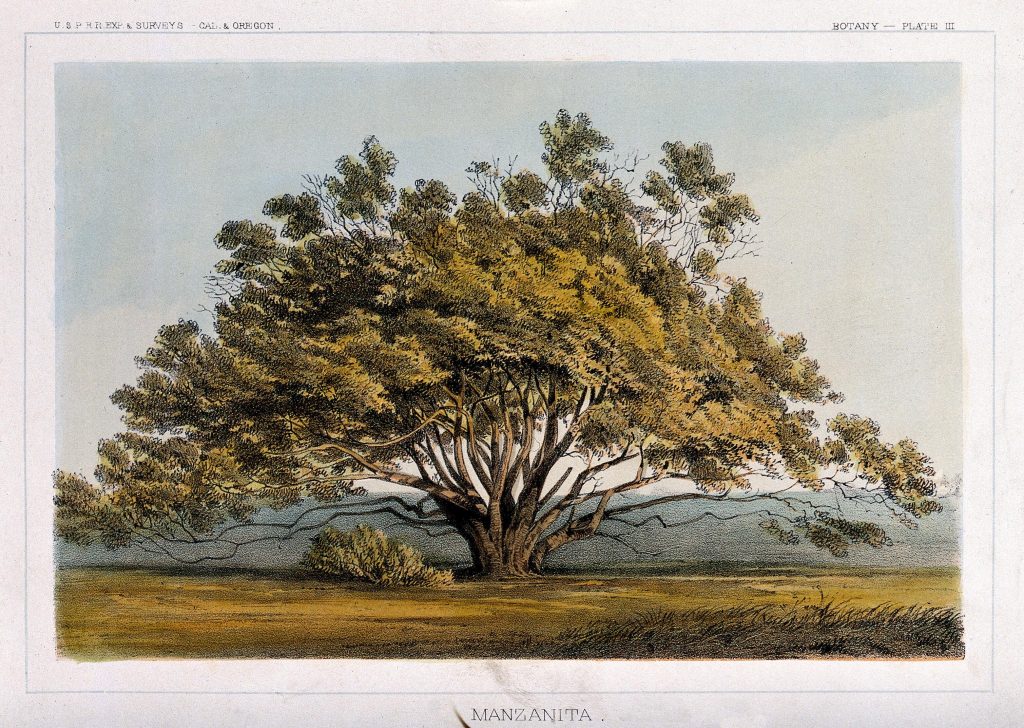

Because manzanita species are so well adapted to their local environment, they cluster into what botanists refer to as “manzanita barrens.” Despite these homogenous barrens, manzanitas readily interbreed where their ranges overlap. This creates a wide variety of physical characteristics. Some manzanitas take the shape of small, low-growing ground covers, while others are trees towering more than 20 feet high.

Manzanitas are most easily recognized by their broad, open structures and red bark branches. In late spring, the tree grows a new ring of wood and a new layer of bark underneath. As the tree expands, the thin layer of outer bark cracks and peels away — or sheds — in small flakes.

Each red branch terminates in one of several tones of gray or green leaves. On hot, sunny days, manzanita leaves will tilt on their edge to reduce overheating and minimize water loss. Native Americans often used these thick and leathery leaves as toothbrushes.

Most manzanitas bloom in the spring, while others flower in the winter. Each tree produces white and pink intensely fragrant blossoms that smell of honey and become focal points for bees and hummingbirds. If you can avoid the bees, squeeze the stem end of a flower to push out a small drop of sweet, honey-tasting nectar.

The name manzanita comes from the Spanish word “little apple,” which describes the tree’s small, apple-shaped fruit produced after the flowers drop. The fruit starts as small, green berries about ¼-inch in diameter. As the fruit ripens over the summer, it turns red and becomes an important food source for quail, mule deer, rabbits, and even bears.

Indigenous people often used manzanita berries to make cider to treat stomach ailments and increase appetite. Even though the berries can be eaten raw (when the fruit turns red), large harvests were dried and ground into a coarse meal used for baking.

Manzanitas rely on wildfires to reproduce. The tree’s seeds have a hard, fire-resistant coating that protects the embryonic seed from heat. The fire also creates small lacerations in that coating and initiates germination. The seeds can lay dormant for up to a century between fires.

The adult manzanita, however, is highly flammable. Oils and waxes on the branches and leaves produce a high-energy combustible fuel that often leads to trees bursting into flames as fire approaches.

This dualistic nature is why some scientists believe the manzanita is one of the world’s rare wildfire misfits. The same wildfire can kill an adult population of manzanita while simultaneously starting the next generation.