The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) tree, which once blanketed the eastern United States for thousands of years, has become the star of an American botanical horror story.

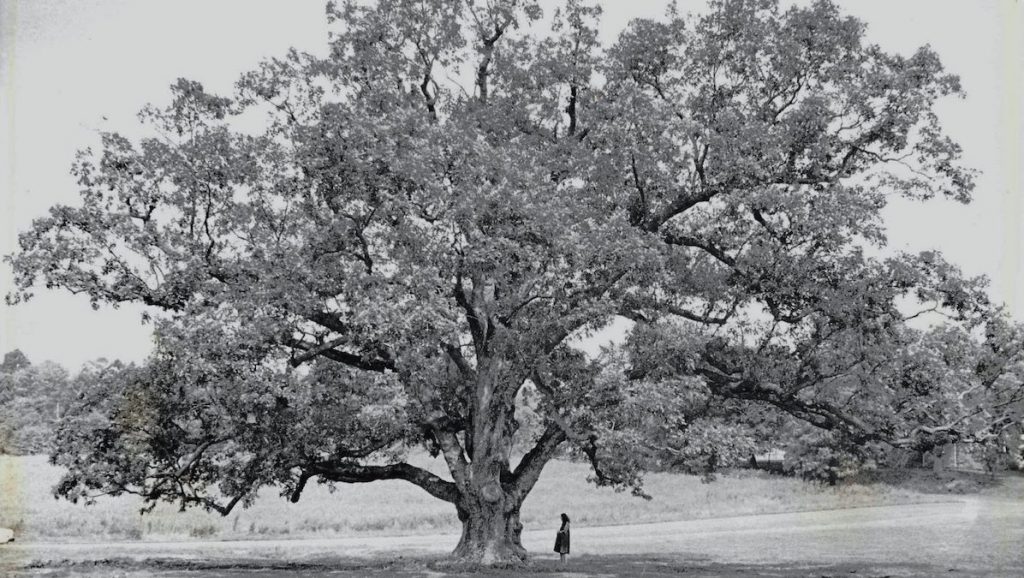

The American chestnut tree, which could reach heights of nearly 100 feet and grow trunks up to 10 feet in diameter, was treasured for its straight-grained and rot-resistant wood. The nuts, which have a creamy and sweet taste, have been enjoyed by wildlife and people alike for thousands of years.

Over a century ago, nearly four billion American chestnuts were growing from Maine to Mississippi. They comprised approximately 25 percent of the trees in the Appalachian Mountains.

Today, there are fewer than 100 American chestnut trees left in existence.

A blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) from Japanese nursery stock was accidentally introduced to the American chestnut in the early 20th century. This fungus was first detected on chestnut trees in the Bronx Zoo in 1904.

In the 1920s, the blight was decimating thousands of trees each year and had reached chestnuts in southern Ontario. By the 1950s, the American chestnut was considered “effectively extinct.”

The fungus had decimated the American chestnut population within 40 years.

The blight fungus kills the chestnut by growing in and beneath the tree’s bark. The fungus enters through wounds on the bark and is first visible as a small orange-brown spot. As the fungus spreads under the bark, a canker forms, giving the bark a tumor-like appearance.

The fungus produces several toxic compounds, including oxalic acid, which lowers the affected tissue’s pH from a healthy 5.5 to a toxic 2.8. This acidity kills the chestnut’s living cells, creating a restrictive girdle of dead tissue. Everything above that girdle dies.

Chestnut blight can kill a tree in as little as four days.

The blight, however, does not kill the tree’s root system. The remaining American chestnuts have survived by sending up stump sprouts. These sprouts eventually succumb to the blight, and the tree dies back to the ground once again, forcing the chestnut to live a Sisyphean existence.

Before the blight, the American chestnut tree was valued for its wood whenever strength and rot-resistance were required. The early American colonists used the chestnut to build log cabins to prevent rotting in the bottom foundation logs. The durable wood was also used for railroad ties.

Ripening in August and September, the American chestnut’s fruit is encased in a spiny capsule called a burr. The burrs are pointed on one end and are approximately one inch diameter with each bur containing two to three nuts.

The burrs fall to the ground after the first frost, where they provided an abundant food source for black bears, white-tailed deer, wild turkey and squirrels of course! One mature chestnut tree could drop as many as 10 bushels of nuts each fall.

Chestnuts are edible raw or roasted, though most people prefer to eat them roasted. The nuts can also be ground into flour for cakes and bread, and added to puddings. Native Americans boiled the leaves and used them medicinally. More than a century ago, train cars full of chestnuts were transported across the country for the holidays. The bulk of today’s 20-million-pound chestnut production comes from imported nuts or hybrid species that have been introduced to the U.S.

The chestnut’s leaf is thin and papery with large prominent teeth on the edge. The leaf contains higher levels of magnesium, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium than other trees in its habitat. When the leaves fall, more nutrients are returned to the soil to help grow different plants and microorganisms.

Several organizations are attempting to restore this iconic American tree to its native range. For more than 30 years, the American Chestnut Foundation has been breeding surviving American chestnuts with blight-resistant Chinese chestnuts. Their goal is to backcross these hybrids over several generations to dilute and eliminate all Chinese chestnut genes except those that provide blight resistance.