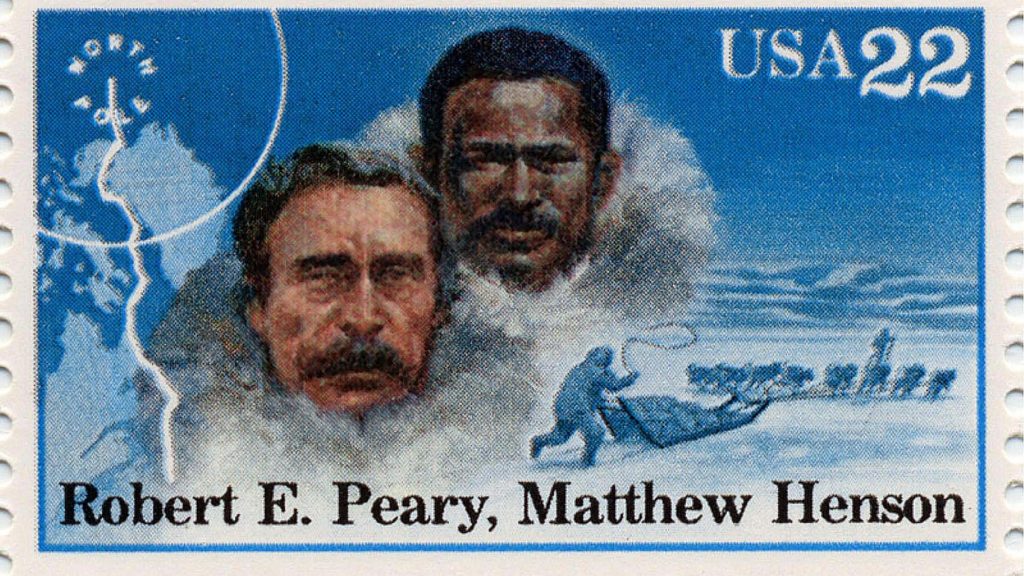

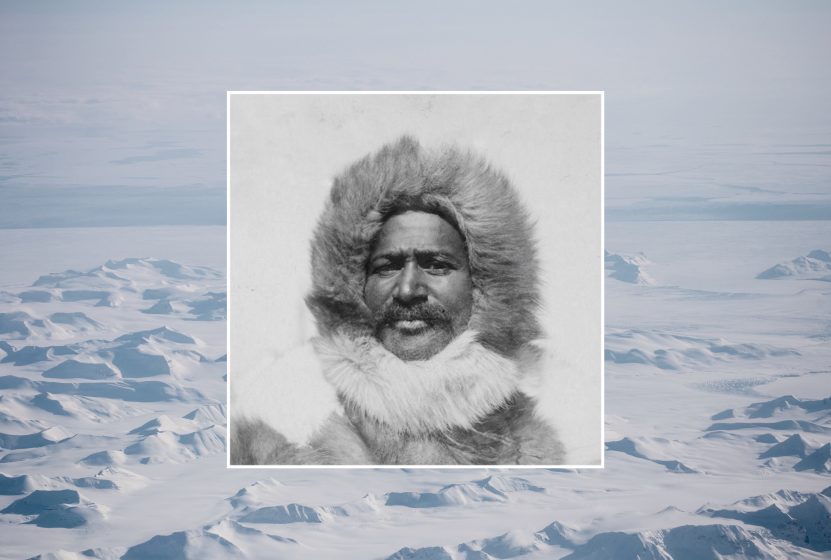

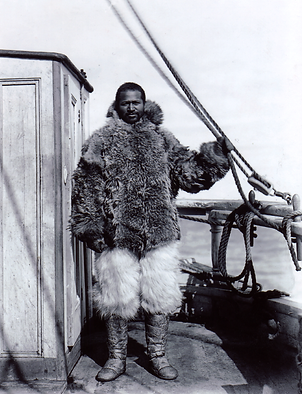

The son of two freeborn sharecroppers, famed African American explorer Matthew Henson was one of the first two Americans to reach the North Pole on April 6, 1909. Henson had been an indispensable member of Robert Peary’s multiple Arctic expeditions and was valued for his polar expertise and relationships with the local Inuit.

Orphaned at 11, Henson worked for a brief time as a dishwasher in a restaurant before walking nearly 40 miles to Baltimore and joining the merchant ship Katie Hines as a cabin boy. The vessel was bound for Hong Kong and became Henson’s home for the next five years.

Henson visited China, Japan, France, Africa, and Russia during his time aboard the three-masted sailing ship. The ship’s captain, Captain Childs, was a Quaker who taught Henson seamanship, reading, writing, navigation, geography, history, and mathematics.

After Childs fell ill and died in 1883, Henson left the ship in Baltimore and joined the crew of a fishing schooner bound for Newfoundland. The captain and crew of the new ship treated Henson poorly, so he left once they arrived in Canada.

Working his way back to Baltimore, Henson found few opportunities in the Post-Civil War reconstruction era. Jobs were scarce, but he ultimately found work in 1887 as a stock clerk in the clothing and hat store, B.H. Steinmetz and Sons.

There, he met a young naval officer, Lieutenant Robert E. Peary. Peary was in the store looking for tropical hats for an upcoming trip to Central America. Impressed by Henson’s seafaring background and Steinmetz’s recommendation, Peary hired Henson to join him as his personal valet on an engineering survey expedition to Nicaragua.

The pair traveled together for the next 20 years, including seven Arctic expeditions between 1891 and 1908.

Between Arctic expeditions, Henson married Eva Helen Flint in 1891 and then quickly rejoined Peary for the duo’s first Greenland expedition.

Henson and Peary returned to Greenland for a second time in 1893, intending to chart the country’s entire ice cap. The team was on the verge of starvation at the end of their two-year expedition, having survived by eating all but one of their sled dogs.

Despite these travails, they returned with another team in 1896 and 1897 to collect three large meteorites they had found during previous expeditions. The meteorites were sold to the Museum of Natural History, using proceeds to fund future expeditions.

Henson’s multiple Greenland expeditions created friction in his marriage, and he and Flint divorced in 1897.

Peary and Henson made several attempts to reach the North Pole. Their 1902 expedition ended with six Inuit members dying once the team ran out of food and supplies.

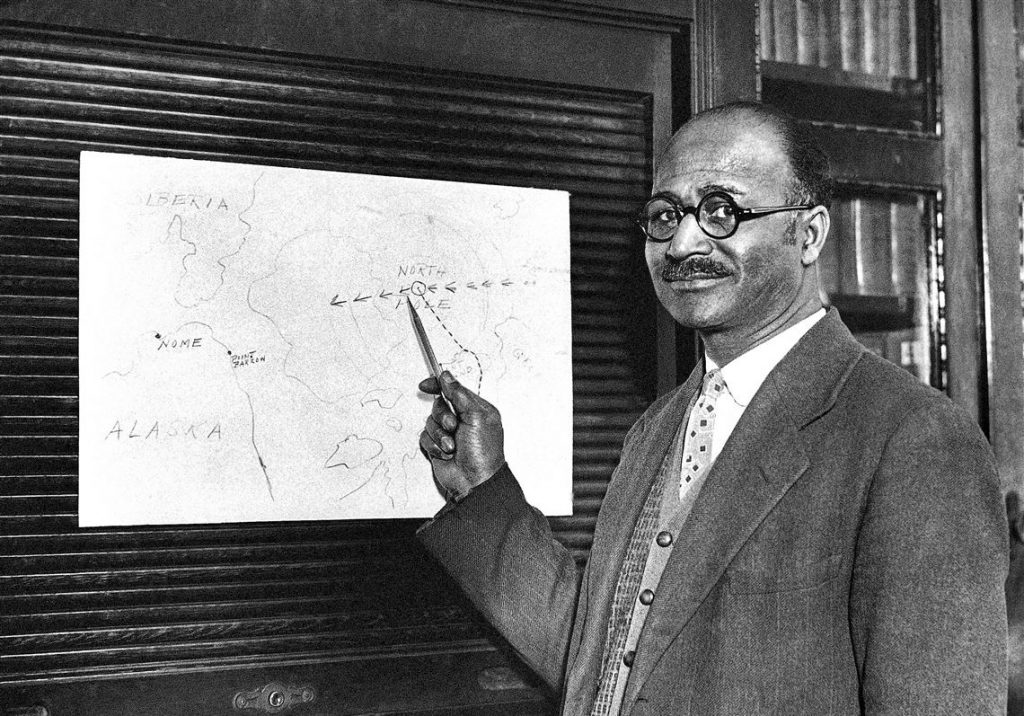

Their 1905 trip was sponsored by President Theodore Roosevelt. Armed with a state-of-the-art ice cutter, Peary and Henson were able to sail within 175 miles of the North Pole before being forced back due to weather conditions affecting the pack ice.

Both Peary and Henson fathered sons with local Inuit women during this trip. Henson’s son, Anauakaq, grew up to become an Arctic hunter and lived in his home village of Moriusaq, Greenland, until his death in 1987.

Upon returning to the United States and before he left for the Arctic expedition that would land him as one of the first men to stand on the North Pole, Henson married Lucy Jane Ross in 1906. He remained married to her throughout his life and had no other children.

After several attempts, Henson and Peary, along with four Inuit aides (Uutaaq, Ukkjaaq, Iggiannguaq, and Sigluk), finally reached the North Pole on April 6, 1909. The expedition began with 24 men, 19 sleds, and 133 dogs and ended with six men and 40 dogs.

Over the two decades Peary and Henson worked together, contemporaries criticized Peary for hiring a black man instead of a white assistant. While some argued that Henson worked for smaller wages as a black man, others point to the fact that Henson was one of the few living men who had the skills necessary to reach the North Pole.

Henson was an accomplished polar explorer who built sleds and repaired them, built igloos, managed sled dogs, made clothing from furs, and spoke the Inuit language.

According to another North Pole expedition member, Donald B. McMillan, Henson “…made every sledge and cookstove used on the route to the pole. Henson was altogether the most efficient man with Peary.”

In addition to his critical contributions to the 1909 expedition’s welfare and survival, Henson saved Peary’s life twice. The first was when Peary nearly drowned, and the second time was when he was attacked by a musk ox. Henson also treated Peary when the expedition leader suffered frostbite and gangrene on the polar ice cap.

Henson was also the most skilled and beloved member of the expeditions when it came to working with the local Inuit communities. Peary was liked for his gifts, while Henson was seen as a friend. The Inuit gave him the nickname Maripaluk, meaning “kind Matthew.”

After his last North Pole expedition, Henson returned home to live a life of relative obscurity, working as a clerk for U.S. Customs.

Henson wrote two books about his arctic explorations. The first was his memoir, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, in 1912. He later collaborated with Bradley Robinson in 1947 to co-write his biography, Dark Companion: The Story of Matthew Henson.

Henson was honored with two Master of Science degrees, one from Morgan State College and one from Howard University. He was also elected as a member of The Explorers Club in 1937. The mittens he wore on the 1909 expedition are displayed at the organization’s New York City headquarters.

Henson was also awarded the U.S. Navy Medal in June 1945, along with other Americans from Peary’s 1909 expedition. He was not invited to the ceremony because he was black.

Henson died in New York City on March 9, 1955, at the age of 88. He and his wife Lucy were reburied with other national heroes at Arlington National Cemetery in 1988.

Today, the USNS Henson, a 329 foot Pathfinder-class oceanographic survey ship sails the world’s oceans conducting research in his name.