The lichen is a remarkable composite organism that can be frequently seen attached to rocks, trees, and even the soil. Often confused for moss, the lichen is actually not a plant at all since it has no roots, stems, or leaves.

Lichens are actually a partnership between two organisms: fungus and alga. The fungi are colorless and thrive on decomposing other organisms. Alga, however, makes its own food through photosynthesis. Partnering as lichen, fungi provides protection to the fragile alga which provides food for both organisms.

A third organism, cyanobacteria, can also be assimilated into the partnership. Since cyanobacteria also contains chloroplasts, it can also harvest light energy from the sun and generate carbohydrates as a food source.

By partnering with alga or cyanobacteria, fungi is able to provide itself with a constant source of nourishment. In return, the alga and cyanobacteria are protected from damaging ultraviolet rays which are absorbed by the fungi.

While there are more than 13,500 species of lichen in the world, with approximately 3,600 species located just in North America, you won’t find lichen anywhere near pollution. The organism only thrives where the air is clean, which is why it is used as a biomonitor to gauge an area’s air quality.

In a process known as biological weathering, lichens break down rocks and release minerals to the soil. They can achieve this through chemical interactions or by the lichen’s ongoing contraction and expansion.

Lichens are found from the arctic tundra to the driest of deserts. Lichen are considered the dominant vegetation in approximately eight percent of the Earth’s land surface.

Unlike most plants, lichen do not have a waxy cuticle on their leaves and they don’t have vascular tissue to transport water and nutrients throughout the organism. Instead, the lichen absorbs what it needs from its surrounding environment through air and rain.

When wet, the lichen’s alga starts photosynthesizing and growing. When the lichen is dry, it goes dormant and becomes brittle. This on and off dormancy explains why some lichen species only add 1-2 millimeters of growth per year. This makes larger lichens extremely old. Some lichens in Greenland are estimated to be between 3,000 to 5,000 years old.

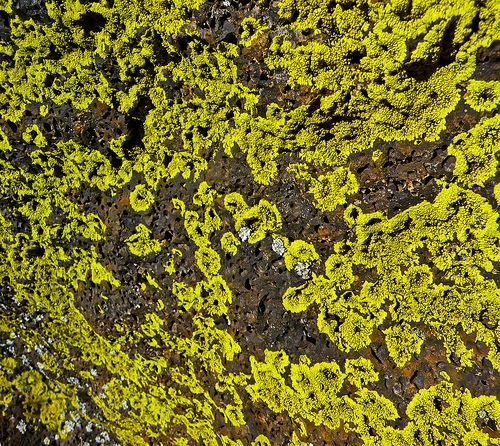

Lichens present a rainbow of colors depending on what special pigments are present in each particular species. Colors vary within species due to age and light exposure with the pigments typically ranging from yellow to orange to red. When those pigments are absent, the lichen will be a gray or greenish gray color.

However, when the lichen is wet, the fungi’s outer layer (cortex) becomes more transparent allowing the underlying alga layer to become visible. Add a little bit of water to a gray lichen and you’ll see the organism come alive in a vibrant green.

The lichen’s vegetative portion is known as the thallus and its shape is what gives each species its characteristic outer appearance — from long looping strands to small bushes to the more common flat crust shape.

The three main types can be described as leafy, crusty, and shrubby.

Leafy, also known as foliose, lichens look like leaves in appearance and structure. They are loosely attached to their substrate by filaments or a single umbilicus.

Crusty, or crustose, lichens are tightly attached to their substrate and make up nearly 75 percent of all lichens on earth.

Shrubby, or fruticose, lichens have no distinct top or bottom. They attach to the substrate in varying ways, from a single umbilicus to hanging over a tree branch. Many of these types of lichens look like hanging moss.

Due to lichen’s hybrid composition, it cannot reproduce like other seed-bearing plants. The dominant fungi can produce spores which will develop into another fungus but that new fungus still has to find an alga to partner with or it will die.

In addition to breaking down their substrates into soil and organic matter, lichens have also provided shelter, nesting material, and food for birds, elk and insects.

Due to their pigments, lichens have been used as a natural pigment for dying fabric, wool and baskets. When mixed with pine sap, or burned to ash, lichens can produce colors like yellow, green, orange, red, purple, and brown.

Some Native American tribes even turned to lichen as a food source when food was scarce.

Not all lichen is edible and some, like wolf lichen and ground lichen, are poisonous. Various tribes used wolf lichen for poisoned arrowheads while others made tea from it. Ground lichen in Wyoming was determined to be the cause of death for 300 “visiting” elk from Colorado in 2004. Local elk had immune systems that could safely process the ground lichen toxins but not so for the Colorado elk.

Lichens are also being studied for their antibiotic properties with new research revealing that these organisms may help fight against specific cancers and viral infections, including HIV.

Dear DRB : Thank You for such an informative article.I always thought those leafy Lichens growing on trees were moss and same with the scrubby ones.Very informative.I have always enjoyed the colorful Lichens clinging to rocks in weird places.Always very beautiful and hardy and determined to survive.Please continue with the outdoor wisdom.Much obliged. Bradford.