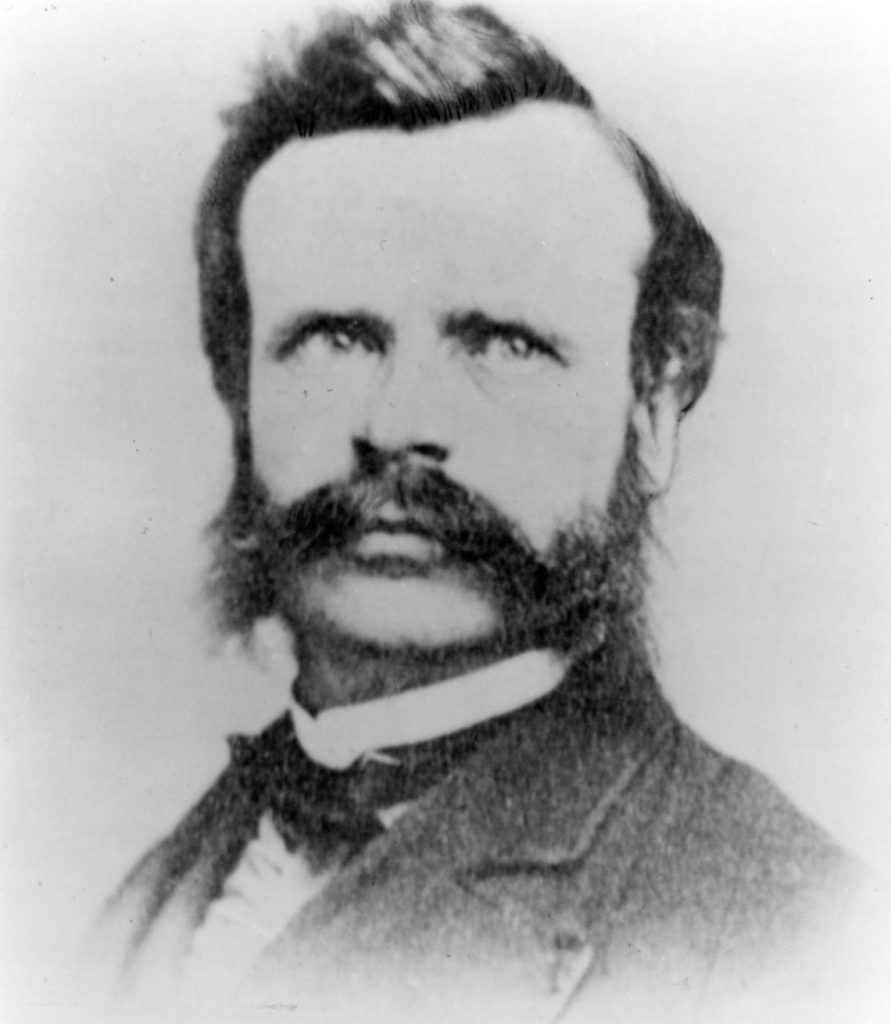

John Wesley Powell was an iconic 19th-century explorer, scientist, and environmentalist. He is best known for his daring riverine explorations of the upper Colorado River and the Grand Canyon.

An adventurer from an early age, Powell walked across the state of Wisconsin when he was 21. The following year, he continued his travels, rowing the entire length of the Mississippi River.

Powell studied Greek, Latin, and Botany at Oberlin but never graduated. He served a brief stint as a school teacher but left to join the Union Army at the onset of the Civil War.

Eleven months after enlisting, Powell had been promoted to second lieutenant. While leading his troops at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862, a Minié ball hit his right wrist, shattering the bones in his forearm. The resulting compound fractures were severe enough to cause amputation below the elbow.

Powell recovered away from the front lines during a six-month recruiting mission. He returned to combat and served in the Battle of Vicksburg in 1863.

After the battle, Powell underwent a second operation on his arm and was promoted to the rank of major during his convalescence.

By February 1865, Powell felt he was no longer able to serve due to his disability. He resigned from the army. The nerve damage and pain in his right arm would plague him for the rest of his life.

He joined the faculty of Illinois Wesleyan University in May as a professor of geology. There, he was able to secure grants for his true passion: field research.

With grant money in hand, Powell started exploring the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. On one of those trips, he met a guide who shared tales about fabled and unexplored areas along the Colorado River. Along those waters were vast plateaus and impassable sections surrounded by towering canyons.

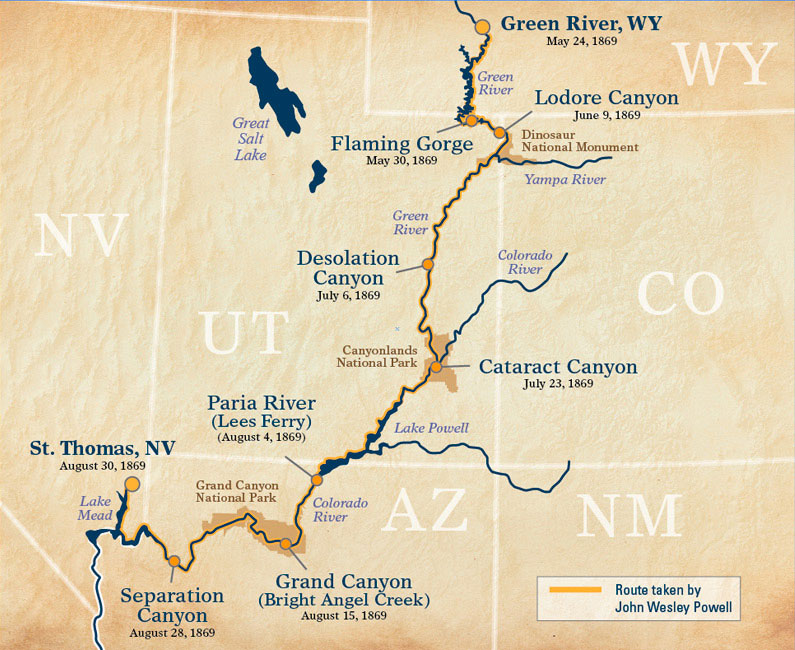

Enthralled by the spirit of discovery, Powell formed a plan to fill in the last big blank spot on the American map. He would float more than 900 miles to map those impassable canyonlands.

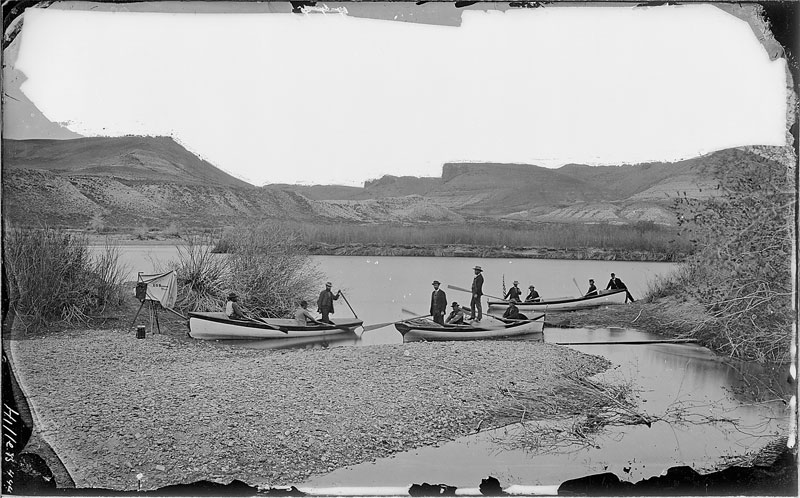

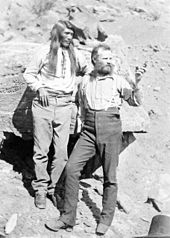

Powell recruited nine volunteers to join him. They were a mix of Civil War veterans, trappers, and outdoorsmen. All had experience hunting and camping. None knew how to run rapids.

The expedition’s four rowboats departed from Green River City on May 25, 1869.

Powell had commissioned the sturdy round-bottomed oak boats for this mission. He had three freight boats — Kitt Clyde’s Sister, No Name, and Maid of the Canyon. Each was 21 feet long and four feet wide. These boats had a decked-over aft and bow bulkhead for storage space. The boats started the journey with 7,000 pounds of food and supplies.

The fourth boat, the Emma Dean (named after Powell’s wife), was 16 feet long and made of pine. This lighter boat was Powell’s personal craft. He had it rigged with a strap he could grab with his left hand for balancing while on the river.

Two weeks and 80 miles into the expedition, the crew experienced their first disaster. Men in the No Name missed a signal from Powell to pull ashore above a rough set of rapids. Frank Goodman, and brothers Oramel and Seneca Howlands, lost control of the boat as it plunged over a small waterfall. The boat hit a rock and split in two. The crew survived, but the supplies and scientific instruments did not. The river claimed maps, firearms, notes from the trip to date, and one-third of their rations.

On July 6, 42 days after the launch, Goodman left the expedition. During a resupply at the Uinta River Indian Agency, he announced he had had enough. He walked away from Powell and went to live with a band of Paiutes in eastern Utah.

After 73 days, the expedition entered the great mystery known as the Grand Canyon. On August 5, 1869 they began a phase of their journey that would have to cross 360 rapids. The Canyon’s lack of beaches and sheer walls would make it almost impossible to portage around violent rapids.

From his river-level perspective, Powell became the first geologist to experience a new view of Earth’s history. At the start, he saw 270-million-year-old Kaibab limestone at water level. As the elevation dropped, the Canyon cut through 19 distinct rock formations. Each formation pushed deeper into the past with each passing mile.

At the lowest point, the basement rocks, the granite has been there for 1.7 billion years. These formations are almost half the age of the Earth and are the oldest exposed rocks in the Southwest.

After three months of rowing, Powell had learned how to read the canyon walls. Horizontal rock layering meant an absence of rapids. When those layers tilted downstream, the river flowed faster. And when the rock layers tilted upward, violent whitewater was ahead.

Two days into the Canyon, the expedition had to cut rations. They had run 10 hardcore rapids as well as replaced the ribs of one of their boats.

Although designed for rough waters, the boats would take on water during each run. Once waterlogged, they became nearly impossible to control. If a boat got turned around and hit broadside by a wave, it would capsize. The crew would have to cling to the overturned boat and rely on its watertight compartments to provide buoyancy.

The near-constant rain also prevented them from building fires most nights. Powell observed that the cold and wet nights exhausted the men more than the day’s travel on the water. The neverending soaking and heating had also ruined their bacon.

Only a few days in the Grand Canyon, the expedition ran into another horrible revelation. Without knowing how much farther they had to go, the men discovered they only had 10 days of rations remaining. Their only source of nourishment was going to be moldy flour, coffee, and dried apples.

On August 27, the crew reached a point that Powell would later name Separation Canyon. Oramel Howlands, the expedition’s mapmaker, confronted Powell about the hazards of continuing. The leaking boats and violent rapids had taken their toll. If Powell didn’t stop, the Howlands brothers and Bill Dunn would hike out on their own.

Powell decided to press on.

The Howlands and Dunn left the expedition on August 28. Declining their share of the rations, they climbed out of the canyon. They would rely on pockets of water and wild game as they trekked 75 miles to the nearest Mormon settlement.

Although they did not know it at the time, the expedition was only days away from calmer waters. The Howlands and Dunn quit 239 miles into the 277-mile Grand Canyon section of the river.

Once the trio left the expedition, they were never seen again.

History offers two differing accounts of their fate.

The first, and most long-held, is that a local band of Shivwit Indians killed them. The men were allegedly mistaken for prospectors who had raped and murdered a woman from the tribe.

The second narrative is that the men were mistaken for federal agents. Some of Mormons who took part in the Mountain Meadows Massacre 12 years earlier, were still on the run from the law. Historians believe these fugitives killed the Howland brothers and Dunn.

Powell was now left without enough men to handle the three remaining boats. He abandoned the Emma Dean and pressed forward.

The following day, Powell’s expedition had reached the Grand Wash Cliffs, marking their exit from the Canyon. The cliffs cross the Grand Canyon where the Colorado River now enters Lake Mead.

In 69 days, the six emaciated survivors had traveled 1,000 miles, lost four of their crew, and half of their boats.

The expedition is considered the last great land exploration in the United States.

Over the next 80 years, only 100 people would be able to complete Powell’s journey. And many more never will. Since 1935, Separation Canyon rapids and those downriver have been entombed beneath Lake Mead.

Powell published a report of his explorations in 1870 in his book “New Tracks in North America.”

Powell’s exploration down the Colorado River led to almost a decade of surveying in the Colorado Plateau region. This body of work was designated the Geographical Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region. It is also more commonly known as the “Powell Survey.”

In 1991, the U.S. Geological Survey completed Powell’s mission of providing 54,000 topographic maps in the U.S.

In recognition of his accomplishments, the Smithsonian Institute appointed Powell to serve as the first director of the Bureau of Ethnology in 1879. He held that post for the rest of his life.

During his work on the Powell Survey, he also collected ethnological information on the Colorado plateau’s indigenous people.

Powell’s new mission was to better understand the tribes and improve communication. He worked to classify their languages and cultures. He wanted scientifically-based ethnology to displace the misconceptions that lead to hostilities between settlers and the tribes.

In 1888, Powell was one of 33 men to found the National Geographic Society. Their goal was to create an organization dedicated to environmental and historical conservation.

Powell also served as director of the U.S. Geological Survey from 1881 to 1894. In that post, he became an influential and controversial advocate for strict water conservation. Powell’s knowledge of the Southwest convinced him that water, or the lack of it, would be a major and ongoing problem in America’s westward expansion.

Powell recommended organizing settlements around water and watersheds. The water would be managed by the private landowners and not the federal government. This would force water users to conserve the scarce resource because overuse would hurt everyone in the watershed. Water rights could also not be sold to faraway cities or syndicates.

Several Western congressmen thought Powell’s ideas were too radical and un-American. They claimed his plans interfered with free enterprise and westward expansion.

If Powell had been successful in implementing his plans, historians believe the western U.S. would be far different than it is today. Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, if they existed at all, would be much smaller, and Phoenix would likely not even exist.

Three months before Powell died in 1902, Congress launched a century of large-scale dam and canal construction. These projects, all subsidized by the federal government, cost billions of dollars. Homesteading consumed the desert Southwest. Desert cities bought up water rights and imported water across hundreds of miles.

Today, several landmarks honor John Wesley Powell’s memory. Namesakes include Powell Plateau, a butte in the Grand Canyon National Park, Powell Mountain in Kings Canyon National Park, California, and Lake Powell which straddles the Utah-Arizona border.