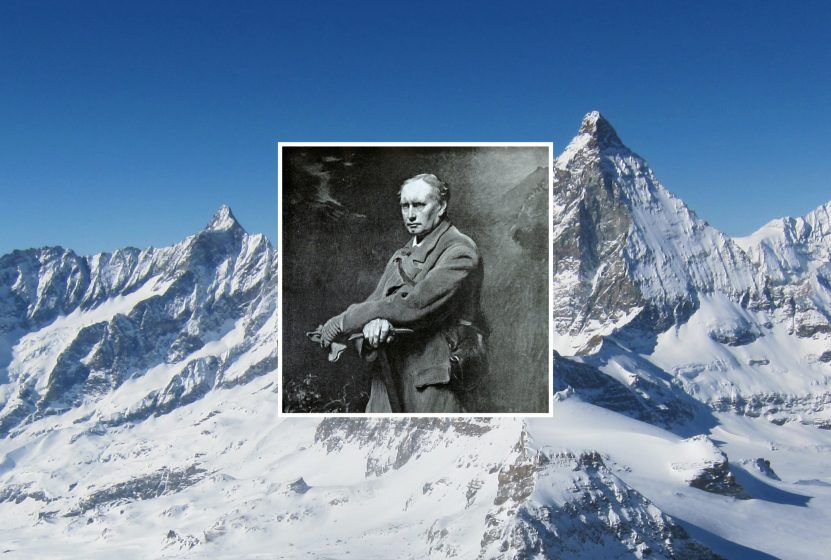

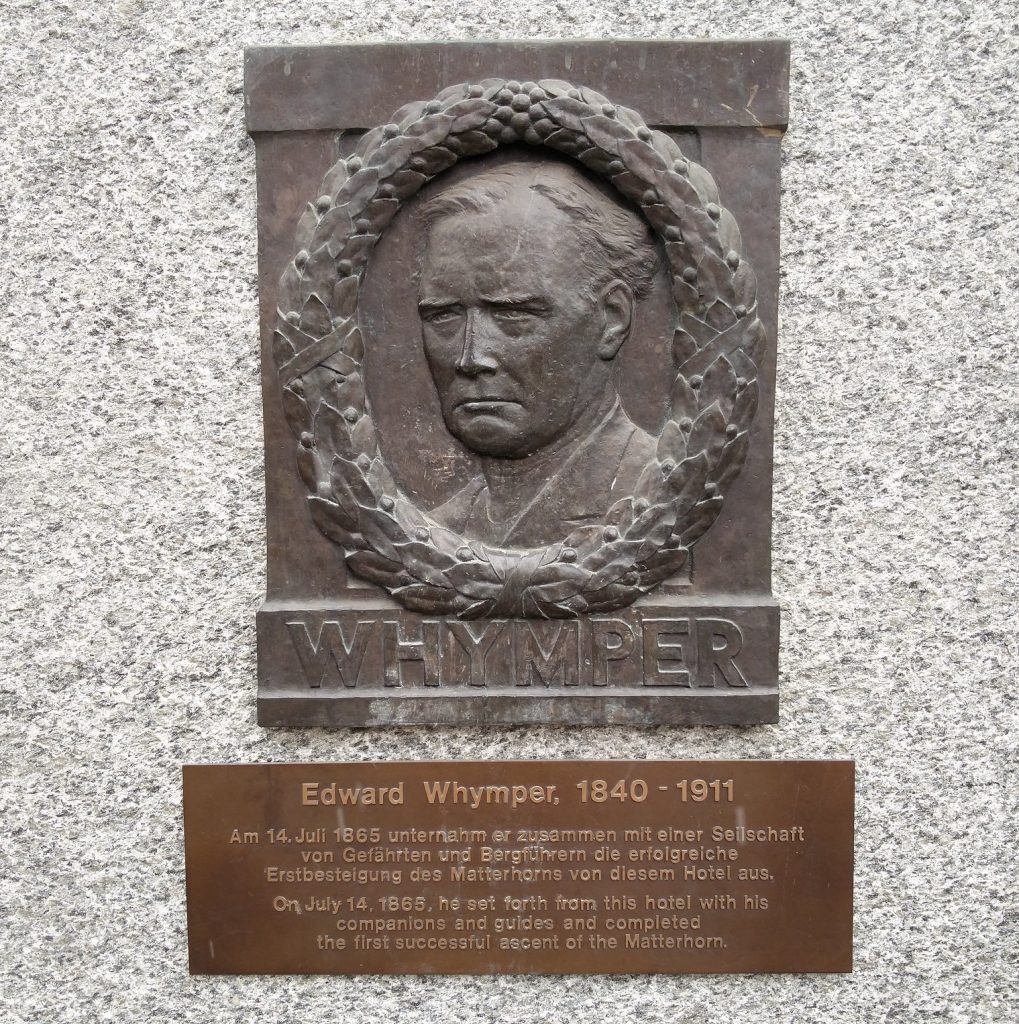

Illustrator-turned legendary mountaineer Edward Whymper (1840-1911) is considered one of Britain’s peak-bagging legends during the Golden Era of climbing. In addition to being the first person to summit the Matterhorn, Whymper’s climbing exploits advanced barometric research and revolutionized high-altitude tent designs.

Born on April 27, 1840, in London, Whymper was the second of 11 children. His father, Josiah, was a painter and engraver. At age 14, Whymper dropped out of school to join his father’s wood engraving business.

Six years into his new occupation, an editor at Longman — a book publisher founded in 1724 — commissioned 20-year-old Whymper to create a series of illustrations of prominent alpine peaks in the Alps.

Whymper immediately fell in love with the area’s rugged peaks upon his arrival in Switzerland. He spent the summer hiking more than 600 miles sketching and scrambling across glaciers and various mountains.

Enthralled by the experience, Whymper returned over the next four summers and started to take climbing seriously. As was common at the time, his only mountaineering gear was a tweed suit, a modified hatchet, ice creepers (spikes driven through the soles of the boots), and a grappling hook.

He also used thick, heavy hemp ropes. Since these woven fiber ropes had no stretch, they were not used for arresting a climber’s fall since the shock load typically resulted in a rope or anchor failure. The hemp ropes were primarily used to create human chains while traversing glaciers and rock ridges.

During these summer visits, Whymper completed the first ascents of Barre des Ecrins, Aiguille d’Argentière, and Mont Dolent in 1864. The following year, he summited Aiguille Verte, Grand Cornier, and Grandes Jorasses, later renamed Pointe Whymper.

By 1865, 15 attempts had been made to summit the 14,692-foot high Matterhorn, which straddles the Italian and Swiss border. Seven of those attempts were even Whymper.

By July of that year, Whymper had decided to change his strategy. He retained the services of an Italian guide to climb the Matterhorn’s Italian ridge. But before the expedition departed, Whymper discovered his guide would leave him for a new, higher-paying client who wanted to make the summit attempt.

Whymper quickly organized another team of eight climbers in Zermatt, the town at the mountain’s base. His objective was to beat the Italians to the summit and become the first human to stand atop the Matterhorn.

Whymper hired Swiss guide Peter Taugwalder and his two sons, Peter and Joseph. He then recruited four other climbers who were in the area and planning their own summit attempts: French guide Michel Croz and Englishmen Lord Francis Douglas, Charles Hudson, and 19-year-old Douglas Hadow.

Just days before, Hudson and Hadow had completed an aggressive climb on Mont Blanc. While the speed of their climb was notable, the effort expended would lead to catastrophic consequences for the Matterhorn attempt.

On the morning of July 13, Whymper’s new team made a mad dash up the mountain’s Swiss side. After 7-½ hours of climbing, the party set up a tent near the base of the peak to spend the night and prepare for their summit attempt early the following morning.

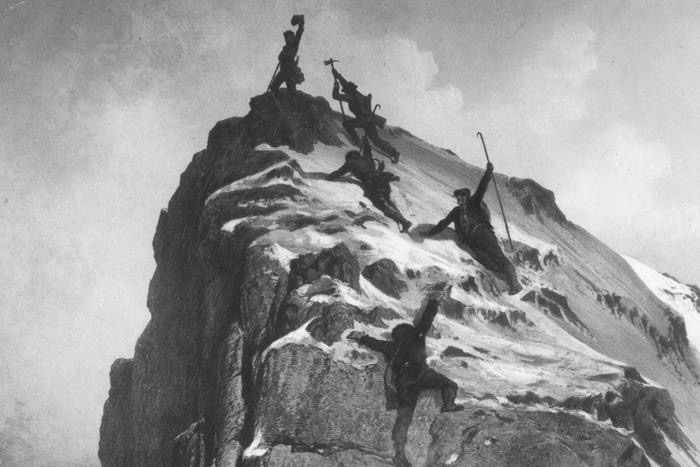

Shortly after dawn, the men started for the summit, unroped. By 1:40 p.m., they had conquered the Matterhorn.

Checking for footprints that would reveal if the Italian climbers had beat him to the top, Whymper peered over the edge and saw the Italians 200 meters below, still working toward the summit.

Whymper and Croz yelled and threw rocks at the Italians to get their attention. Once the Italian guide saw Whymper beat his team to the summit, he turned around and led his team back down the mountain.

After staying for an hour on the summit, Whymper and his team began the long descent. The men were tied together with hemp rope, Croz in front, followed by Hadow, Hudson, and Douglas. Next was the senior Taugwalder, Whymper, with Taugwalder’s son.

The young Hadow, allegedly fatigued from his Mount Blanc climb, needed extra assistance during the descent. His worn shoes kept slipping, so Croz had to help him secure his feet. Croz had to lay down his ice axe every time he did this.

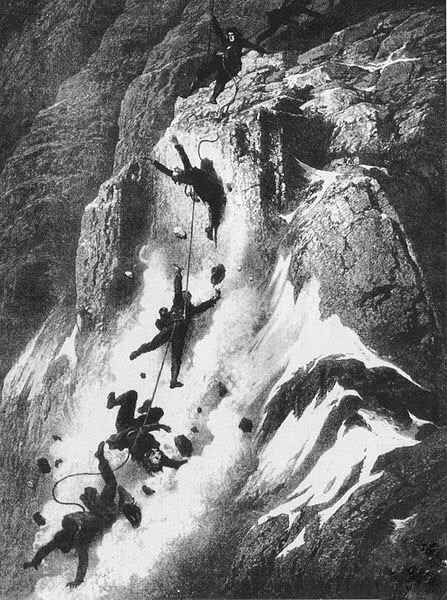

At 3:45 p.m. — the moment imprinted on the crushed pocket watch of one of the victims — Hadow slipped again and slammed into Croz. Croz lost his footing and fell headlong down the steep slope, pulling Hadow, Hudson, and Douglas with him.

Hearing Croz yell, Taugwalder and Whymper latched onto nearby rocks to arrest the men’s fall, but the rope broke.

Whymper watched Hadow, Hudson, Douglas, and Croz slide downwards on their backs, frantically clawing at the snow to save themselves. One by one, they fell off the precipice and landed on the Matterhorn glacier nearly 4,000 feet below.

In shock, Whymper and the two Taugwalders fixed their remaining rope to rocks, then continued the descent before finding a resting place to spend the night at 9:30 p.m.

The surviving expedition members reached the town of Zermatt on the morning of July 15, and a rescue attempt began that afternoon. Volunteers saw the men’s bodies lying on the snow near the plateau of the Matterhorn Glacier and retreated back to town before dark.

Early Sunday morning. Whymper led the recovery effort to find his fallen teammates. Upon reaching the glacier’s plateau, Whymper found the bodies of Hadow, Hudson, and Croz. The only sign of Douglas was his sleeve.

The bodies were recovered on Wednesday, July 19. Douglas’ body was never found.

Later, Whymper examined the hemp rope that had connected the team during the descent. He discovered that Taugwalder had used the oldest and weakest rope in the team’s arsenal. This rope had only been intended as a reserve. Stronger ropes had tied the fallen men together, while the weaker reserve rope was the one that connected Douglas to the elder Taugwalder.

The Matterhorn tragedy immediately became a media sensation. Peter Taugwalder became the subject of an investigation on allegations he cut the rope to save himself. He was eventually cleared of responsibility but shunned by other mountaineers. He soon quit his guiding job and emigrated to America.

The accident drew so much media attention that Queen Victoria even asked her advisors to draft laws to prevent her subjects from participating in mountaineering and climbing.

After the accident, Whymper shied away from the Alps. He continued to run his family’s engraving business and organized expeditions to explore the coastline and interior of Greenland.

In 1880, he completed the first ascent of Ecuador’s Chimborazo (20,549 feet). During his South American trips, Whymper started studying the scientific effects of altitude on humans.

In 1892, Whymper published “Travels Amongst the Great Andes of the Equator.” Considered his finest work, the book blends Whymper’s illustrations and his scientific inquiries and recollections of Ecuadorian climbs investigating altitude sickness. The book earned him the Patron’s medal from the Royal Geographical Society for groundbreaking work on living in high elevations.

Whymper later published “How to Use the Aneroid Barometer” for climbers and guide books for Chamonix and Zermatt.

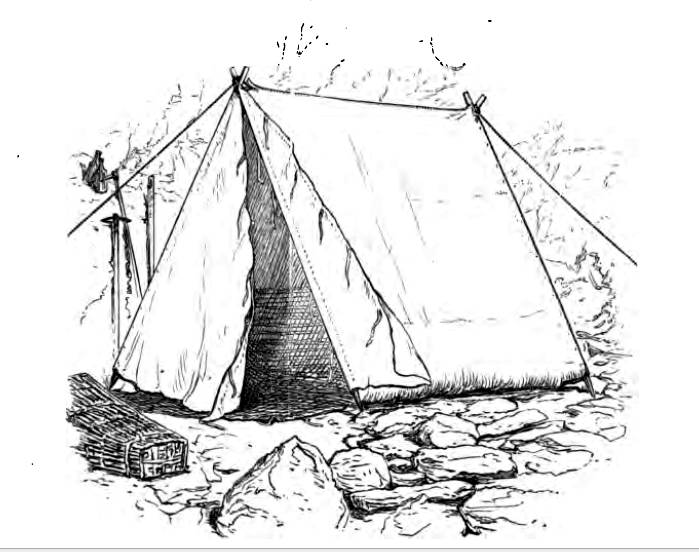

Whymper also designed an A-frame mountaineering tent known as the Whymper tent. During Whymper’s Era, there were no tents suited for the harsh conditions found in mountaineering. Most tents were large, unwieldy, and designed for the military.

Whymper’s tent was held up with two crossed poles and a climbing rope as a ridgeline. The tent was made of canvas with an integral Mackintosh groundsheet and weighed 22 pounds — dry.

The Whymper tent revolutionized mountaineering since it was relatively light with high stability and wind resistance at altitude.

In the early 1900s, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) hired Whymper to conduct trail explorations and surveys in the Canadian Rockies that would help develop tourism in the area. The CPR also paid Whymper to promote the Canadian Rockies and the rail line during his lectures in Europe and Asia.

During his trips to Canada, Whymper made the first ascents of Mount Whymper and Stanley Peak in the Vermilion Pass area of the Canadian Rockies.

Despite his scientific work, Whymper’s most famous book is “Scrambles Among the Alps,” published in 1871. In addition to over 80 illustrations by Whymper, the book includes a detailed account of his experience in the Alps from 1860-1869, including the tragic event that haunted him for the rest of his life.

“Every night, do you understand, I see my comrades of the Matterhorn slipping on their backs, their arms outstretched, one after the other, in perfect order at equal distances-Croz the guide, first, then Hadow, then Hudson, and lastly Douglas. Yes, I shall always see them…”

Later in life, Whymper returned to the Alps every summer. After a climb in Chamonix in 1911, he returned to his room at the Grand Hotel Couttet and died at the age of 71.