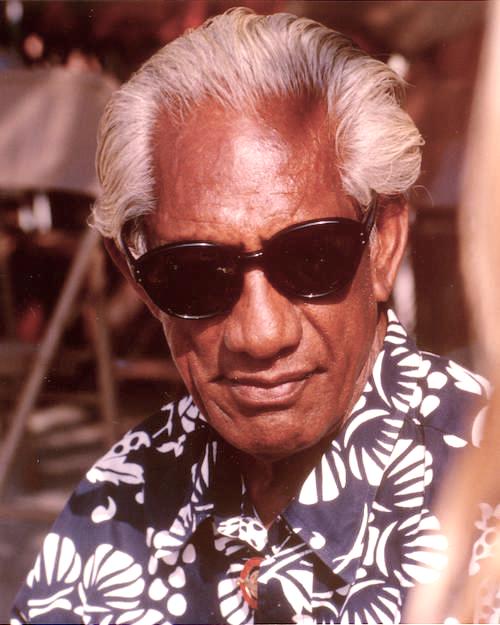

One of the world’s most renowned watermen, Clyde “Duke” Paoa Kahinu Mokoe Hulikohola Kahanamoku, changed how we view and engage with oceans today. As a five-time Olympic medalist, rescue swimmer, and the father of modern surfing, Kahanamoku defined the standard of the 20th-century Renaissance aquatic athlete.

Born in Honolulu, Hawaii, in 1890, the same year the United States annexed Hawaii, Kahanamoku grew up in a family of prominent swimmers. His father, Charles, was a local champion swimmer and surfer. His brothers, Nai and Kan, also became champion swimmers.

On August 11, 1911, Kahanamoku broke the world record in the 100-yard freestyle swim by 4.6 seconds. In addition to having a six-foot, one-inch tall physique and size 13 feet — perfectly built for propelling him through the water — the 21-year-old used a combination of the Australian crawl stroke with a double-flutter kick.

Later called the “Kahanamoku Kick,” this version of the Australian crawl helped him easily beat the competition in swimming events.

His record-breaking swim was so impressive that the American Athletic Union (AAU) disallowed it, concluding that currents and timekeeping errors contributed to his feat.

The Hawaii community rallied behind Kahanamoku and raised money to send him to the U.S. mainland in 1912 to demonstrate to the AAU his skills in the water were indeed real.

Kahanamoku’s muscles cramped during his first national pool competition, and he had to be rescued from the water.

He tried later in the week and won the 50-yard and 100-yard races he entered.

These wins caught the attention of George Kistler, the University of Pennsylvania swim coach. Kistler worked with Kahanamoku to improve his turning technique, breathing, and diving.

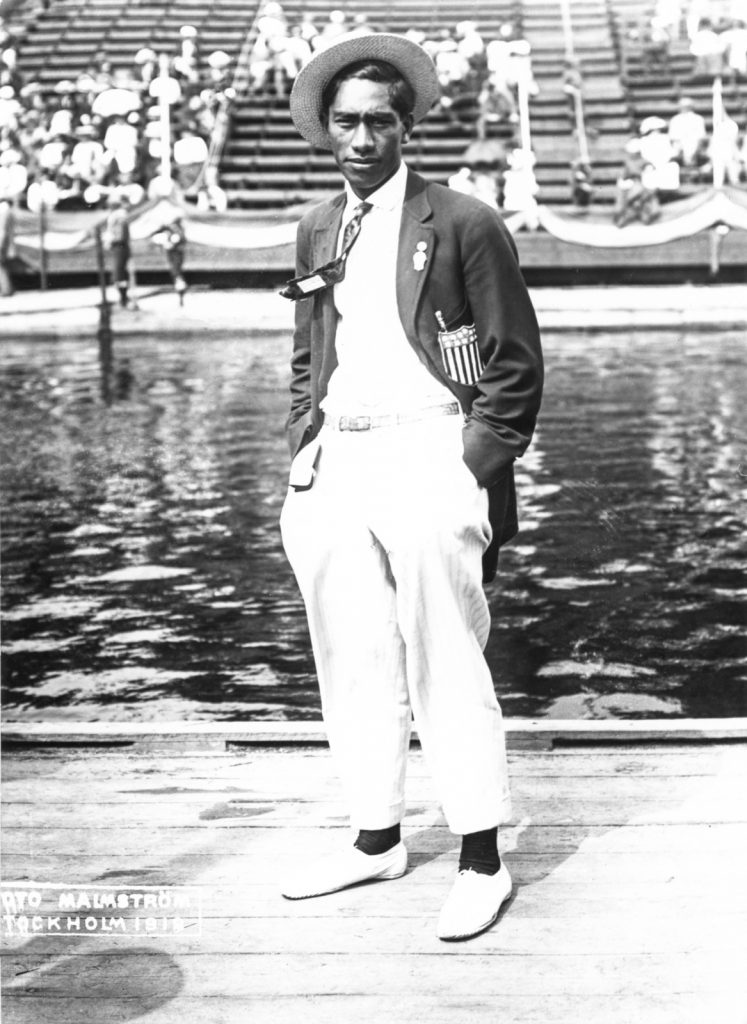

Less than a month under Kistler’s tutelage Kahanamoku earned a spot on the U.S. Olympic swim team. In 1912, at age 22, he went on to win a gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle and a silver medal in the 4×200-meter freestyle relay at the Stockholm Olympics.

Buoyed by his Olympic success, Kahanamoku invested the next four years of his life in training for the 1916 Summer Olympics that were to be held in Berlin, Germany. Unfortunately, the games were canceled with the First World War raging across Europe.

Kahanamoku then shifted his sights to the 1920 Olympics and spent the intervening years raising money for the American Red Cross by giving swimming and lifesaving performances across the globe.

Contracting the Spanish Flu in 1918 put a temporary halt to his training. Kahanamoku eventually recovered and went on to compete in the 1920 Antwerp Olympics. He won the gold medals in the 100-meter freestyle and 4×100-meter freestyle relay.

Kahanamoku returned to the 1924 Games in Paris, where he won the silver medal in the 100-meter freestyle. Johnny Weismuller, the future star of the “Tarzan” movies (1932-1948), captured the gold medal, and the bronze went to Kahanamoku’s younger brother, Samuel.

Kahanamoku made one last appearance in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. At age 42, the five-time Olympic medalist served as an alternate on the U.S. water polo team.

Although he introduced longboards to the United States and Australia in 1914, Kahanamoku’s wave riding influence increased after he retired as an Olympian and traveled the world teaching swimming and sharing the Hawaiian sport of surfing.

Kahanamoku’s early surfboards were made of redwood or pine and were between 12 to 16 feet long. His longer redwood surfboards weighed up to 100 pounds.

Kahanamoku also taught Australian lifesavers how to use the longboard as a rescue tool effectively. While the Aussies had acquired a surfboard while visiting Hawaii in 1912, they didn’t know how to use the board to its fullest potential. When Kahanamoku visited Australia in 1915, he showed the lifesaving teams how to use the surfboard to transport distressed swimmers to shore.

In 1925 in Newport Beach, California, Kahanamoku used that technique to save eight people when a squall capsized a 40-foot sport fishing boat. He made eight trips through the stormy surf, dragging passengers onto his board, and kept venturing out into the swells to recover the bodies of those who perished.

Newport’s police chief declared Kahanmoku’s feat the “most superhuman surfboard rescue act the world has ever seen.”

After that event, American lifeguards started using surfboards as part of their rescue efforts.

Kahanamoku was cast in several minor Hollywood film roles in the 1920s and played himself a few times in the 1950s and 1960s.

Hawaiians elected him to serve as sheriff of the city and county of Honolulu in 1934, and he remained in that office until 1960.

When Hawaii became the 50th U.S. state in 1959, Kahanamoku was named the official State of Hawaii Ambassador of Aloha.

He later survived brain surgery and danced the hula with Queen Elizabeth II of England before dying of a heart attack on January 22, 1968, at 77.

As a testament to his widespread impact and influence on swimming and surfing, Kahanamoku was the first person inducted into both the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1965, the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame in 1984, and the Surfers’ Hall of Fame in 1994.

Since longboard surfing led to modern-day skateboarding, snowboarding, and even skysurfing, many board enthusiasts believe Kahanamoku is the father of all board sports.

In 1999, Surfer Magazine named Kahanamoku “Surfer of the Century.” In 2000, Sports Illustrated honored him as Hawaii’s “greatest sports figure of the century.” Today there are no less than three statues celebrating the Duke; one in his hometown of Waikiki, another in Huntington Beach, and a third at Fresh Water Beach Australia.