The art of strapping two sticks on your feet and traversing snowy landscapes has been infuse by humans for nearly 7,000 years. While skis have allowed people to hunt, gather firewood, and travel quickly on snow, using cross-country skis is also one of the more physically taxing activities.

Cross-country skiing uses more muscle groups than any other sport, except perhaps long-distance swimming. Using your legs and arms to propel your body across snow can burn approximately 600 calories per hour for the average person. To put that in perspective, running a 10-minute mile for an hour will get you close to 500 calories. Elite cross-country athletes, however, can burn about 1,300 calories per hour.

Skiing’s origins are credited to early Scandinavian and Siberian inhabitants. Norse mythology even credits Ullr, Thor’s stepson, as the god of Winter, hunting, hand-to-hand combat, and skiing.

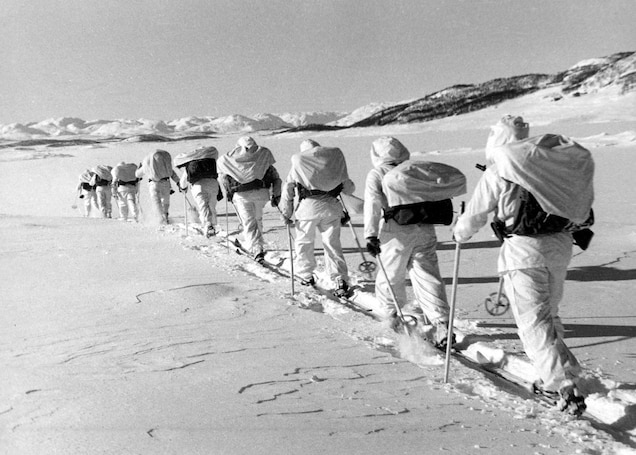

Ullr’s combat and skiing DNA must have been flowing through the veins of Nordic ski commandos in World War II. In February 1943, nine Norwegian saboteurs armed with explosives, grenades, submachine guns, pistols — and their cross-country skis — destroyed a Nazi heavy water plant near Telemark. The facility was a critical part of the German’s plans to develop nuclear weapons.

After blowing up the plant’s heavy water supply, the team escaped to the nearby countryside. More than 3,000 soldiers were sent in pursuit. Four of the nine commandos hid in the mountains and continued to lead further operations against the Nazis. The five remaining commandos took to their skis. For 18 days, the men skied across the mountainous and frigid terrain, covering 280 miles, as they made their escape to Sweden.

While the Norwegian team may have been using cambered skis, which, ironically, were invented in Telemark in 1850, their equipment had probably not changed much since Urll’s days.

For centuries, skis were made from two thin boards and attached to the feet with lashings of rope or animal hide. The word “ski” comes from the Old Norse word “skíð,” which means a split length of wood.

The skis varied in length but were typically close to 10 feet long. Archaeologists have determined that there were at least three main types of skis based on the regions in which they were developed: southern, central Nordic, and arctic. The southern and central Nordic types had one ski shorter than the other. The short ski was often covered with animal skins to help climb steep terrain, while the longer ski was gliding. Arctic skis were short, generally of equal length, and also covered in fur.

Fur was mounted on the ski’s bottom with the hair pointing toward the heel. In this orientation, the hair grabs the snow when the ski moves backward or against the hair’s grain. When the ski rolls forward, the hair flattens and allows some glide. Backcountry and cross-country skiers still use this mechanism today but with synthetic hair that is attached with buckles, straps, and adhesives.

By the early 1700s, skiers began using skis of the same length. The equipment and techniques would continue to rapidly evolve over the next 150 years.

By 1741, the lone spear or long pole used to aid the skier’s balance, braking, and turning was replaced by two pine or bamboo poles. Steel poles were developed in the 1930s and were later replaced by lighter weight aluminum poles in 1959. Today, skiers use carbon fiber and Kelvar wrapped poles that combine light weight with strength and stiffness.

Another challenge for earlier skiers was that their skis were made out of wood. Wood absorbs moisture, freezes, and creates unneeded friction on the snow.

Sami skiers from Lapland were reported in 1674 to have found a solution to this dilemma by using pine pitch and rosin to protect their ski bottoms and improve glide.

Pine pitch, which was later replaced by wax and perfluorocarbons, glides on snow because it repels water. Water beads on the pine tar-treated ski bottom instead of forming sheets. These tiny water droplets act like microscopic liquid ball bearings allowing for a faster glide.

Although Norwegian emigrants brought skis to America as early as 1825, they were not a popular mode of winter transportation for several years. In the 1850s, California gold miners started using their skis for winter entertainment. To pass the cold and snowy days, they invented a type of straight-line downhill racing. These miners didn’t care about maximizing traction on their skis. They were after maximum glide. By 1868, they were testing anything that would make their ski bottoms slicker: kerosene, oil, candle wax, and glycerin. They even tried spermaceti, the waxy stuff found in the heads of sperm whales.

At about the same time miners were rocketing down the California mountainsides, Norwegians were mixing cross-country racing with ski jumping.

These competitions required the athletes to use the same skis for both cross-country and jumping. As the jumps became longer and cross-country skiing became faster, racers had to adapt their equipment. Racing skis became narrow and lighter while jumping skis grew wider and heavier to increase higher launch speeds.

Before the end of the 19th century, ski builders started using laminated wood construction, which led to lighter and stronger skis. Regardless of ski construction, there was no real distinction between downhill (alpine), cross-country (Nordic), or backcountry skiing until the early 1900s. Skiers simply skied up and across the terrain using a shuffling motion with their feet attached to the ski.

In 1927, Bror With created the Rottefella binding, which replaced the heel strap with a three-pin front binding. This binding was fixed to the skier’s boot with three holes drilled in the sole.

Sonder Norheim, another Norwegian ski innovator, invented a two-part binding. His system used one leather strap over the top of the boot. A second strap wrapped from one side of the front foot, around the back of the ankle, and to the other side of the foot. This allowed the toe of the foot to stay attached to the ski while the heel could rise.

This new binding led to the development of the kick-and-glide (skate skiing) method. Although in use for decades, skate skiing wouldn’t gain much popularity until the 1980s. It has since become the fastest technique in cross-country skiing and is preferred among competitive and elite skiers.

Perhaps it’s that mix of effort, outdoors, and movement that continues to attract thousands of new skiers to cross-country skiing every year. The global cross-country ski equipment market was $6.8 billion in 2020 and is expected to grow to $8.3 billion by 2026.

Even though the techniques and equipment continue to evolve, cross-country skiing doesn’t get any easier. Maybe that’s why today’s cross-country devotees are motivated by a passion that has been pursued by both mythological and modern skiers alike: Nothing approximates the sensation of flight without wings like cross-country skiing.