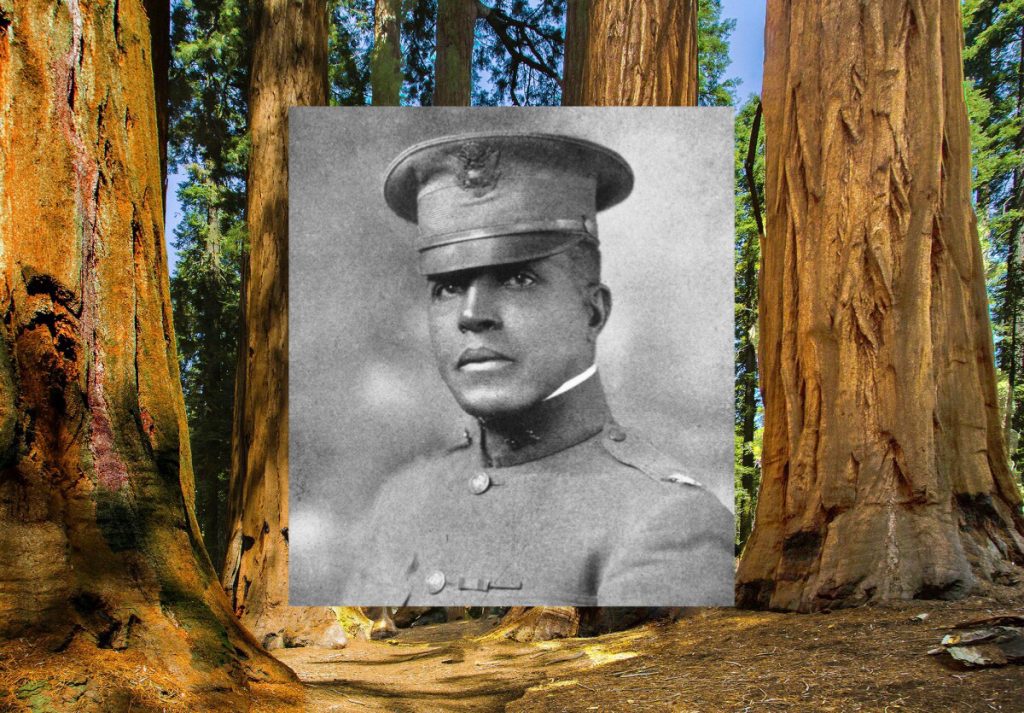

Born into slavery, Charles Young became one of America’s top military leaders while facing nearly insurmountable social barriers. Young was the third African American West Point graduate, the first black military attaché, the highest-ranking black officer in the regular army, and the first black U.S. national park superintendent.

Charles Young was born in 1864 in Mays Lick, Kentucky. His father Gabriel escaped from slavery in 1865 by crossing the Ohio River. He enlisted in the Union Army’s 5th Regiment of Colored Artillery (Heavy). His military service earned the family’s freedom through the 13th Amendment.

Discharged from the army in 1866, Gabriel moved his family to Ripley, Ohio.

Charles Young excelled in languages and music while attending the town’s integrated high school. When he graduated with academic honors in 1880, he was fluent in Latin, Greek, Spanish, French, and German. Young was also the first African American to graduate from the school.

Following graduation, he taught in the town’s black high school for the next four years. Inspired by his father’s military service, however, Young left teaching and entered a competitive exam for a cadet appointment at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Only the top-ranked candidate in each exam pool would be accepted.

Young had the second-highest exam score.

When the top candidate decided to not take the appointment, Young jumped at the opportunity. He reported to the military academy in 1884.

Called “The Load of Coal” by his classmates, Young was tormented and isolated by both students and faculty. He often found solace conversing in German with some of the school’s servants to maintain a basic level of human interaction.

Young graduated with the class of 1889, becoming the third black man to graduate from West Point. The next would be almost 50 years later.

Upon receiving his commission as a first lieutenant, Young was assigned to the 9th U.S. Cavalry (nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers”) at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, for one year. He then served at Fort Duchesne in eastern Utah from 1890 through 1894.

In 1894, Young was appointed to lead the new military sciences department at Wilberforce University in Ohio. There, he became close friends with a fellow faculty member and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), W.E.B. Du Bois.

When the Spanish-American War kicked off in 1898, Young accepted a promotion to the temporary rank of major. He took command of the 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry which was preparing to join the fight in Cuba. By the time the 9th mobilized, the four-month conflict had ended.

Young then reverted to his regular army rank of first lieutenant in 1899. He received a promotion to captain in 1901. As a captain, Young led the 9th Cavalry’s troops in the Philippines during the Philippine-American War. His actions earned praise from his commanders for his men’s courage and professionalism in combat.

In 1903, he accepted the command of a segregated black company at the Presidio in San Francisco. At the time, he was the only black captain in the U.S. Army. While there, he received orders to move his troops to Sequoia and General Grant (now Kings Canyon) National Parks for the summer.

Like all national parks at the time, Sequoia National Park was under the Interior Department’s purview in 1890. The department received no Congressional appropriations to manage the parks. Sequoia was ripe for plunder and was plagued by poachers, illegal loggers, and fires.

Those damaging activities almost came to a halt the following summer when the U.S. Army Cavalry took over management of the national parks. Serving a one-year assignment, military officers managed the national parks from 1891 to 1913.

After a 16-day ride from the Presidio, Young arrived at his next assignment with the men of the 9th Calvary’s I and M troops. Over the previous three summers, Young’s predecessors had completed less than five miles of a wagon road to the park’s Giant Forest.

Within six weeks, Young’s troops completed the Giant Forest road and had extended it to the base of Moro Rock. The road allowed the wealthy and powerful to visit the park for the first time. This led to more support for the young park and Congressional lobbying to increase funding. Young’s roads, although improved in later years, are still in use today.

Young’s troops also built a trail system to the top of the highest mountain in the nation at that time, Mt. Whitney.

With the new visitors walking through the park, Young observed people trampling over the giant trees’ shallow roots. He built the first fences to protect the most exposed trees, General Sherman and General Grant. Today, the General Sherman Tree is the world’s largest tree standing at 274 feet and is approximately 3,500 years old. The General Grant Tree is now the world’s third-largest tree at 268 feet and is approximately 1,670 years old.

Young encouraged the Interior Department to buy more land to expand the park’s boundaries. He was unsuccessful although the park ultimately purchased the same land at later dates and at a much higher price.

After completing his tour at Sequoia National Park, Young wrote in his final report, “Indeed a journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are.”

A visiting group of local business leaders wanted to name one of the giant sequoia trees after Young in honor of his work. He refused, and recommended a tree should be named after “that great and good American, Booker T. Washington.”

The Booker T. Washington Tree eventually became lost to obscurity for most of the 20th century. The tree was re-discovered in 2000.

Impressed by his leadership at the national parks, the army assigned the young captain to serve as the military attaché in Haiti in 1904. There, his mission was to observe foreign armies and report on their training, exercises, strengths, and weaknesses.

In 1908, Young returned to 9th Cavalry to command his troops in the Philippines, Wyoming, and Texas until 1911.

From 1912 through 1916, Young served as military attaché to Liberia. He trained the Liberian Frontier Force, a militia formed a century earlier by black colonists from the United States.

When he returned to America, Young was promoted to lieutenant colonel, becoming the first black officer to achieve that rank in the U.S. Army. He took command of the 10th Cavalry Regiment’s 2nd Squadron and led his men into combat during the Pershing Punitive Expedition in Mexico.

During the Battle of Agua Caliente, Young led his troops in the first cavalry charge since the Spanish American War. Drawing their .45 cal pistols, Young and his men charged 150 of Pancho Villa’s villistas, scattering the opposing forces and ending the battle.

When Young returned to the U.S., America was on the verge of entering World War I in Europe. Anticipating a need for more African American officers, he opened an officers training school for enlisted men.

At his core, Young was a soldier and wanted to lead troops into battle. He applied for a command in Europe and expected to a promotion to the rank of general. The War Department did not want the possibility of a black army general leading white troops into battle. Their solution was to take Young off the playing board. They forced him into medical retirement due to “disabilities.”

To protest that decision and to prove his fitness for duty, the 54-year-old Young rode 500 miles on horseback from Ohio to Washington, D.C. Although the War Department did not reverse his medical retirement, they did promote Young to full colonel.

In 1918 they sent Young to Ohio to muster and train black troops for the war, months before the armistice was signed.

In 1920, the State Department requested Young’s help in Liberia. Due to his previous experience there, he was assigned to serve another military attaché tour in the West African country. Suffering from kidney disease the last several years of his life, Young fell ill and died during a reconnaissance mission to Lagos, Nigeria, in 1922. At the time of his death, Young was the highest-ranking black officer in the U.S. Army.

When Young’s body returned to the U.S. in 1923, approximately 50,000 people lined Manhattan’s streets in tribute to his life. Young’s funeral service was held at the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater, making him the fourth person to receive that honor. He is buried in Section 3 of the Arlington National Cemetery.

Young finally received recognition at the park he had helped protect nearly 100 years after serving as its acting superintendent. In 2004, a large sequoia tree was designated the Colonel Young Tree. His tree can be found off the Mora Rock Road that his troops built a century before.

In addition, the California State Legislature renamed a part of Highway 198 the Colonel Charles Young Memorial Highway. This section of the road starts at Salt Creek Road and leads to the Sequoia National Park entrance.