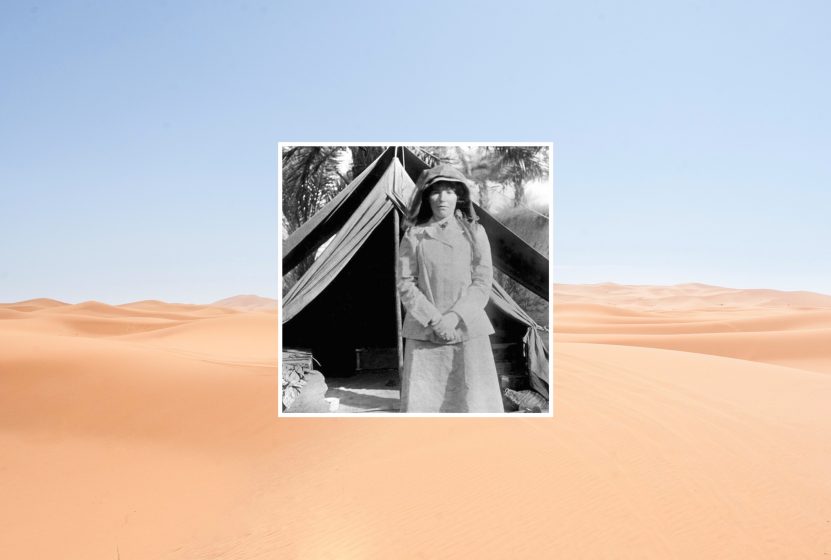

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926) was a Victorian-era trailblazer who left the posh comforts of her wealthy British family for a life of exploration, archaeology, and political service. She authored several books on the Middle East and played a critical role in establishing modern-day Iraq after the First World War.

Gertrude Bell was born in Washington, England, to an affluent and politically connected family. She attended Queen’s College and then Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford University for her formal education.

Bell graduated with a modern history degree in 1892 and was one of the first two Oxford women to graduate with first-class honors.

Immediately after leaving Oxford, Bell went to Persia (modern-day Iran) to visit her uncle, Sir Francis Lascelles. He was serving as an embassy minister at the time. Her first book, Persian Pictures: From the Mountains to the Sea (published in 1894), features Bell’s sketches and explores the country’s heroic past and prolonged decline.

Bitten by the adventuring bug, Bell left Persia to mountaineer in Switzerland. She climbed the highest peak in the Alps, Mont Blanc. She then gained some celebrity after a summit attempt of the unclimbed northeast face of the Finsteraarhorn. A sudden summer blizzard pinned Bell and her team on the highest mountain in the Bernese Alps, clinging to a rope for 53 hours.

Bell’s love for history led her back to the Middle East in 1899. She visited Syria and Palestine and explored the historic cities of Damascus and Jerusalem. These experiences led her to a deeper understanding and passion for the region’s culture and people.

During this time, Bell became fluent in several languages, including Persian, Arabic, Turkish, French, Italian, and German.

In 1907, Bell began working on excavations in Turkey with Sir William M. Ramsay, a Scottish archaeologist considered one of the foremost authorities of his time on Asia Minor history and the New Testament.

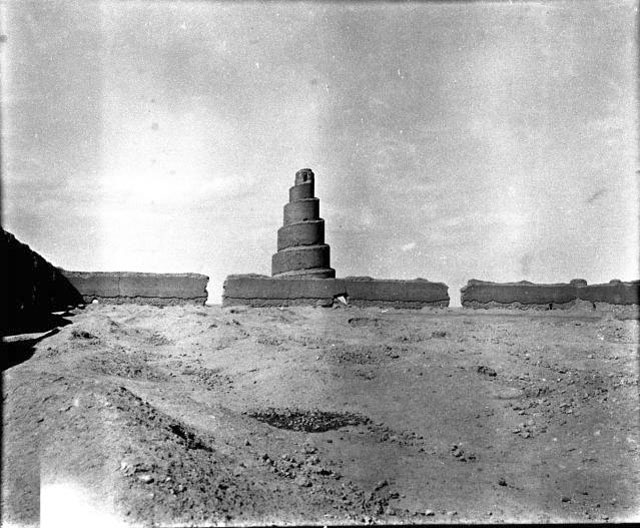

She then shifted her focus to Mesopotamia (roughly modern-day Iraq), the land between the Tigris River to the east and the Euphrates on the west. She studied and mapped ancient ruins in Carchemish, Babylon, and Najaf.

She completed her four-year Middle Eastern journey in 1913 by traveling 1,800 miles from Damascus to Ha’Libecame, the second non-native woman to visit Ha’il in northwestern Saudi Arabia.

When the First World War kicked off on July 28, 1914, Bell wanted a diplomatic posting to the Middle East. Her requests were denied, so she volunteered with the Red Cross and worked in an auxiliary military hospital established in the home of Lord and Lady Onslow at Clandon Park.

Frustrated by the low level of work she was doing at the hospital — sorting and distributing books to the patients — Bell pushed for a position closer to the front lines in France.

That request was eventually granted, and in November 1914, Bell received instructions to report to the Red Cross headquarters in Boulogne, France.

When she arrived in France, Bell was 46 years old.

She wanted to contribute more to the war effort than working as a field hospital secretary.

After all, In the years leading up to the Great War, she had commanded desert caravans. She mapped Middle Eastern terrain with great precision during her previous exploits. She studied the geography of the region and the politics of the tribes. Her cultural awareness, political savvy, and excellent language fluency allowed her to build relationships with local tribes that many of her male contemporaries could not.

Bell’s past eventually caught the attention of British Intelligence. They needed someone with her Middle Eastern experience to help soldiers successfully navigate the desert. With her close relationships with locals and tribal leaders in Syria and Mesopotamia, Bell was made a political officer in the British forces in Cairo — the only woman with that distinction during the war.

When British troops captured Baghdad in 1917, Bell was appointed Oriental Secretary for High Commissioner of Iraq. Her assignment was to assist in the restructuring of the former Ottoman Empire.

As a reward to the various Arab tribes that had joined the British under T.E. Lawrence (aka “Lawrence of Arabia”) to overthrow the Ottomans, the British had promised the groups the right to self-governance at the war’s end.

In 1919, Bell authored the report “Self Determination in Mesopotamia,” which ultimately led to the creation of modern-day Iraq.

Despite Bell’s experience with the region and its people, vital elements of her report were unfortunately ignored by British leadership. Bell soon realized that Britain had promised an Arab government with British advisers but intended to create a British government with Arab advisers.

Britain’s objectives were formalized at the Cairo Conference of 1921 — which included Bell, Lawrence, and Winston Churchill as delegates. A plan was approved that divided the former Ottoman territories into two. Each region would be ruled by a prince in the Hashemite family. Prince Faisal I bin Al-Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi, who worked with Lawrence during the war, would be the leader of a new country called Iraq. His brother, Prince Abdullah, would lead Transjordan (now Jordan).

Bell believed that none of the proposed borders would satisfy every faction, and long-term peace would be improbable. However, she was determined to see the new country succeed, so she continued as Oriental Secretary.

Bell made Baghdad her permanent home and became an advisor to King Faisal. She helped to write Iraq’s constitution and organize elections. Her deep knowledge of the culture and language allowed her to effectively deal with the various Iraqi factions and interests, earning her the nickname “al-Khatun,” or “Lady of the Court.”

Another result of the war’s conclusion was an excavation frenzy by American and European archaeologists across Iraq. Bell wanted to keep the artifacts in the country, so she worked with King Faisal to create the Iraqi Archaeological Museum (now the National Museum of Iraq). She also supervised excavations, donated several items from her personal collection, and served as director of antiquities.

Eventually, the desert heat and Bell’s heavy workload affected her health. Suffering from rapid weight loss and recurring bronchitis, she gave up her post and returned to England.

Upon her landing in 1925, she found her family’s fortune, made primarily in the iron industry, was in a downward spiral. Labor strikes and economic depression across Europe had taken their toll on the family’s businesses.

Bell soon developed pleurisy, an inflammation of the membranes surrounding the lungs. Shortly after she recovered from the illness and returned to Baghdad in 1926.

She stayed out of politics, but in June, presided over the opening of the museum’s first antiques room.

Weeks later, she was found dead on the morning of July 12 from an overdose of sleeping pills.

Gertrude Bell was buried in Baghdad’s Bab al-Sharji district at the British cemetery. She was posthumously awarded the Order of the British Empire.