America’s rarest native pine, the Torrey pine (Pinus torreyana), is only found in two locations in North America. One population grows on the coastal bluffs of Soledad Valley, north of San Diego, California. The second population is on Santa Rosa Island and is separated from the first by 175 miles of Pacific Ocean.

The tree is named after American botanist John Torrey, who first described the pine in 1853 while he was a member of the Mexican Boundary Survey — the most comprehensive vegetative examination completed along the new 1,969-mile border between Mexico and the United States.

Today, both Torrey pine populations are believed to be left-over fragments, or relict populations, of a past population that once covered a larger area of southern California.

Due to thousands of years of separation from each other, the Santa Rosa population is genetically different enough from the mainland trees. It is a separate subspecies and has been given the common name of Santa Rosa Island Torrey pine.

There are approximately 3,000 Torrey pines between both populations, with numbers as high as 9,000 trees in the 1970s.

The decline of the Torrey pine is attributed to air pollution, fire, drought, and several bark beetle infestations.

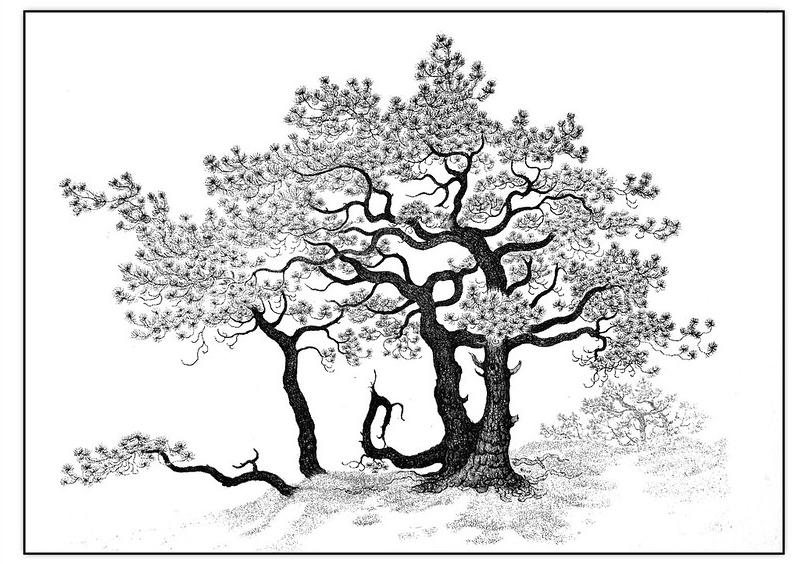

Shaped by coastal winds, the Torrey pine often has a twisted trunk with bent branches and may never reach 25 feet in height. Its bark ranges from reddish-brown to reddish-purple and is deeply furrowed with irregular scaly ridges.

The tree’s green-gray needs are 10-12 inches long, organized in bunches of five. The Torrey pine’s needles live for three years and turn brown before falling off in the autumn of their third year.

The Torrey pine’s needles appear to be perfectly designed for capturing moisture from fog. The larger needle and more needles per bundle create more surface area to contact and capture fog. The needle’s surface structure is covered with microscopic channels that run its entire length. The tiny fog droplets are captured and merged into larger drops that flow down the channels and drop to the ground to water the soil at the tree’s base.

The Torrey pine’s reproductive structures are called strobili. Characterized by overlapping scalelike parts, the strobili form female and male organs. The male strobili are arranged into a slim, cylindrical flower cluster with no petals. This cluster, or catkin, produces pollen distributed by the wind.

The Torrey pine’s female strobili are located farther out on the tree’s branches. These are shaped like a prickly ball approximately ½ inch in diameter. The female strobili are red when young and then fade to green to brown as they mature over three years into a 6-inch cone.

The scales of the Torrey pine cone have a stout tooth-like tip. Two large dark brown seeds are protected at the base of each scale. The seeds are slowly released over 10 years. While the seeds have a wing, like other pine trees, the Torrey pine’s wing is small and easily separated from the seed. This may be why the tree’s propagation depends on scrub jays and small animals for seed distribution.

Historically, members of the Kumeyaay tribe collected the Torrey pine’s seeds, or pine nuts, in the fall as a food source. The seeds were consumed raw or cooked. The tree’s needles have also been used for weaving into open coiled baskets.

The Torrey pine is a critically endangered species with a declining population. Due to the small numbers and geographic isolation, each of the two populations has become genetically inbred and lacks the diversity to withstand disease, pests, or ecosystem changes.

Botanists are currently a decade into an experiment that may reverse the Torrey pine’s decline. Researchers are attempting to cross-breed the two populations together to boost genetic diversity. This practice is known as “genetic rescue” and has successfully been used to rebuild populations of the Florida panther and greater prairie chicken.