The world’s hardiest plant lives on Kafeklubben Island, off the coast of Greenland. Located just over 83 degrees north and closer to the North Pole than any other land on Earth, this island is made of permafrost whose summers only last around 30 days. Here, the purple saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia) thrives and brings a splash of vibrant color to an otherwise gray and rocky vista.

In Latin, Saxifraga means “rock breaker,” and this hardy little plant lives up to its name. Purple saxifrage grows on exposed rock, cliff crevices, gravel, and even on moving surfaces like scree slopes.

The purple saxifrage is common in the high Arctic and also some high mountainous areas further south, including northern Britain, the Alps, and the Rocky Mountains. The plant inhabits temperate and Arctic zones from sea level to more than 3,000 feet.

The purple saxifrage has also been found growing at 14,780 feet in the Swiss Alps. This makes it the highest elevation angiosperm — a plant that flowers and produces seeds — in Europe. Even the plant’s roots are exposed to temperatures below minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit at this altitude.

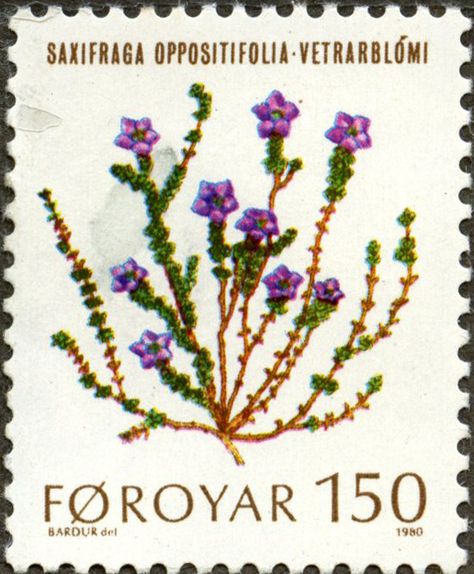

The purple saxifrage is a densely matted plant that only grows to about two inches high. The small round leaves have ciliated margins and are positioned in four rows close to the surface. Growing this low to the ground protects the plant from evaporation and abrasion from wind-driven snow or sand.

In spots where the purple saxifrage’s taproot is anchored in limestone, the leaves extrude small pieces of calcium carbonate. This extreme weather adaptation allows the hard white reflective mineral to shield the plant against wind and intense solar radiation.

Perfectly adjusted to the short growing season, the purple saxifrage’s flowering buds survive the winter protected by the plant’s own foliage. Once the snow cover melts, the buds quickly bloom with individual flowers lasting about 12 days.

The purple saxifrage’s flowers are about ½ inch in diameter. They are among the first spring flowers to bloom and appear in April in alpine environments and June in the Arctic. In northern Canada, the purple saxifrage’s bloom often coincides with caribou calving, a trait the Inuit have used as a time-keeping device to mark the annual event.

The purple saxifrage grows slowly, only putting out two pairs of new leaves each growing season. This means a plant only four inches wide can be several decades old.

The purple saxifrage propagates from both cross-fertilization and self-fertilization. In temperate environments, the plant is cross-fertilized from pollen carried by bumblebees and butterflies early in the flowering season. Near the end, the pollen transport is handled by smaller flies. The stems are sticky to prevent crawling insects that aren’t pollinators from stealing the Saxifrage’s nectar.

The purple saxifrage self-pollinates in the alpine and Arctic environments where insect activity is limited. The stigma (female reproductive organ) matures first, allowing pollen from other plants to be carried by insects or the wind. If no pollen arrives within four days, the plant’s anther (male reproductive organ) lengthens and curves inward to self-fertilize.

In addition to using the purple saxifrage bloom to mark caribou calving, indigenous people use the plant in various ways. The sweet flower petals are eaten by residents in Nunavut, formerly part of the region of northern Canada known as the Northwest Territories. The petals, called aupilaktunnguat by the Innuit, are reportedly bitter at first but become sweet-tasting after a second or two.

The Inuit also brew the leaves and stems for herbal tea, with the best-tasting tea coming from late summer flowers that have died on the plant.

Unfortunately, the purple saxifrage’s ability to withstand extreme cold could also lead to its extinction. With polar and high-altitude regions warming faster than other parts of the globe, the hardy little Arctic plant is encountering fierce competition from invasive species.

A recent study from Parks Canada that tracked the flowering season of purple saxifrage over 20 years showed little to no adaptation to the earlier start of the season. Other invasive plant species are adjusting to the longer growing season and moving north, putting the future of nature’s hardiest plant at risk.