Winter is coming.

The cold, snow, wind, short days, and lack of fresh food have made winter a survival challenge for every species on the planet. While humans have used technology to prevail in harsh climates, wildlife never had that luxury. They have had to adapt to these seasonal changes through various physiological and behavioral modifications.

However, recent genetic and anthropological research has revealed that nature has also revamped the human body to endure life in the cold zone.

Here are five ways animals, including humans, deal with the depths of winter.

1. Get out of town

If you can’t handle the cold, it’s time to pack your bags and head south for the winter. Like New Yorkers who escape cold weather by moving to Florida for the season, wildlife also heads to warmer climes for survival.

One of the main reasons animals migrate is to find food. For example, humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) swim to summer feeding grounds near the polar ice to feast on small fish and krill. They return to warmer waters in the winter to give birth and raise their calves. Some whales make round trips of up to 10,000 miles.

Approximately 4,000 species of birds migrate every year. The world record holder for migrations distance is the Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea). Averaging 44,000 miles every year as it flies from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and back, this tiny bird spends most of its life in the air.

Another epic airborne migrator is the Monarch butterfly(Danaus plexippus). These insects have a 3,000-mile migration route that stretches from Canada to Southern California and Mexico. Since these butterflies typically only live 2 to 6 weeks, the migration takes place over several generations. The butterflies stop to lay eggs on milkweed plants along their route. When the eggs hatch, the young caterpillars eat the milkweed, form their chrysalis, and within 14 days, emerge as butterflies to continue the migration.

2. Sleep it off

If animals don’t have the body type for covering long distances, they have to stay home for the winter and find a way to survive on little to no food. Animals like bears, mice, skunks, turtles, and frogs survive winter by entering a state of dormancy called hibernation.

Contrary to popular belief, hibernating animals don’t actually sleep through the winter. For example, Alaskan brown bears (Ursus arctos) just get extraordinarily sleepy and lethargic. They lower their body temperature by 8-12 degrees, and their bodies break down fat stores for fuel to consume for the 2-5 months that winter lasts. During this hibernating period, bears will stay in a den and not eat or drink. They also rarely defecate or urinate.

Bears do move around inside the den during hibernation. They periodically wake to shift body position to better conserve heat and prevent pressure sores from developing.

Not all bears hibernate. If food is available, some bears will reduce their activity and sleep more than usual but will still be out and about foraging during the winter.

3. Shelter in place

Some animals can’t migrate or build up enough fat stores to survive winter, so they need to find a way to avoid the bitter cold.

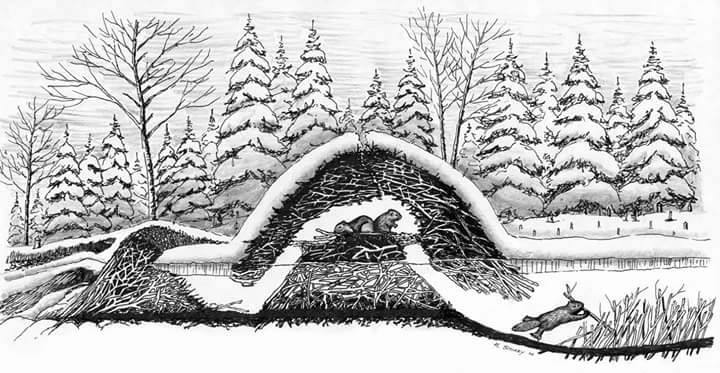

Beavers (Castor canadensis), the civil engineers of the wild, hunker down inside their intricately constructed and bomb-proof lodges. Before the beaver’s pond freezes, these semi-aquatic rodents store fresh willow, alder, birch, and poplar branches in the deepest part of their pond to protect their winter food supply. Once the top of the pond develops an ice cap, the beaver simply swims under the ice to the cache and brings fresh food into the lodge for family mealtime.

Muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus) will sometimes sublease space in a beaver lodge during the winter. Muskrats bring in reeds and other foliage to help shore up the lodge’s interior. The muskrats get a safe and warm winter haven in exchange for their tenant improvements and even share the beaver’s food.

4. Change your body

Other animals have evolved to survive the cold through unique physiological adaptations. While most frogs spend winter hibernating deep underwater, their body temperature never falls below freezing.

The wood frog (Lithobates sylvaticus) uses a different strategy. Instead of living underwater, this amphibian buries itself in leaf litter on the forest floor. While the leaves and snow provide some insulation from the cold, the frogs are not as protected as they would be if they were surrounded by water. As a result, the wood frog’s body freezes solid and can remain in the frog-sicle state for up to eight months.

The winterization process starts with the wood frog’s internal organs getting encased in ice. The frog’s liver flushes large amounts of glucose into every cell just before it freezes. This syrupy sugar solution acts as an antifreeze to keep the cells from freezing and binds water molecules inside the cells to reduce dehydration.

On the other hand, the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) has its own version of internal antifreeze and stays active year-round. Found deep in Arctic waters, the Greenland shark is the second-largest carnivorous shark after the great white and is also the slowest swimming with an average cruising speed of 0.75 mph.

This shark prefers water between 32-50 degrees Fahrenheit and has a lifespan of more than 200 years. The Greenland shark can thrive in this frigid environment because their bodies contain high levels of trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), which makes their flesh poisonous to eat, but also works as a natural antifreeze.

Fun fact: Early Greenland and Iceland settlers found a way to safely consume this shark by burying the meat in the ground for 2-3 months. By exposing it to several cycles of freezing and thawing and then hanging it to dry for several more months, the meat is ultimately cut into bite-sized morsels known as the cultural delicacy, Hákarl.

On the terra firma side of winter, mammals rely on insulation to retain body heat and dense fur for protection from the elements.

The polar bear (Ursus maritimus) has a thick coat of insulated fur that covers a warming layer of fat. An extra evolutionary bonus is black skin which better absorbs the sun’s warming rays.

Penguins also have a dense layer of blubber under their thick skin to provide insulation. Instead of fur, they have four layers of tightly packed and overlapping tiny feathers that provide warmth and waterproofing. Penguins also huddle together in large groups to preserve their collective body heat. These adaptations allow them to survive temperatures as low as -94 degrees Fahrenheit.

5. Use technology…while nature forces adaptations

Over the millennia, humans emerged from a tropical environment and moved north. Since our bodies are poorly adapted to the cold, we’ve had to develop strategies that focus on controlling the environment around us.

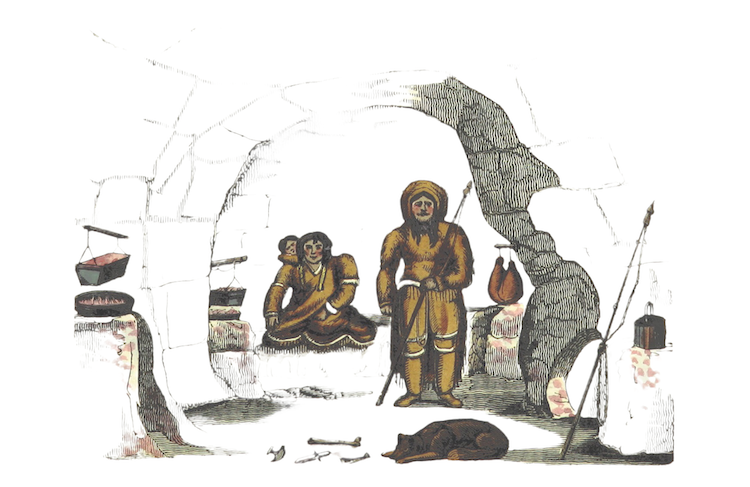

Like other mammals, we’ve migrated south to warmer climates. We’ve also attempted to mediate winter’s effects by building warm structures, fabricating insulating clothing, and using fire to provide external heat sources.

We’ve also changed our behaviors and adapted to a more meat-centric diet to replace the fruits and plants that don’t exist at higher latitudes.

Nevertheless, evolution has also forced our bodies to deal with colder climates as our species moved north. Research suggests that early subsets of humans crossbred with Denisovans, an extinct species of human that ranged across Asia more than 150,000 years ago. These interspecies liaisons ultimately led to a boosted immune system, changes in skin color, and cold tolerance adaptations.

Tibetan populations, for example, have the EPAS1 gene, which allows them to function at higher and colder altitudes. This gene is thought to have originated from Denisovans, and breeding with other hominids gave modern man the genetic secret sauce for braving the cold.

Similarly, many Greenlandic Inuits have genetic similarities to Denisovans which allows them to increase heat generation from body fat. These genes, specifically TBX14 and WARS2, are divergent from nearly every other human population.

Recent research also reveals that our ancestors may have been hibernators. Anthropologists believe some early humans coped with hardcore winters by slowing down their metabolism and sleeping for months on end. Bone analysis of our hominid predecessors in northern Spain revealed lesions and other signs of damage that were consistent with those left on the bones of other hibernating animals.

The bone markings revealed seasonal variations in bone growth. These disparities suggest that growth was disrupted for several months each year during a period of lowered metabolic states that are typically seen in other hibernating animals.

While some may believe the connection between reduced bone growth and hibernation is tenuous, scientists point to the hibernation attributes of other primates like bushbabies and lemurs. The genetic basis and physiology for lowering metabolism exist in many mammalian species and could easily include humans.

What about the modern Inuit and Sámi people?

They live in arguably colder and harsher conditions but don’t hibernate.

The answer is diet.

These indigenous people eat reindeer fat and fatty fish during the winter. This food provides enough nourishment that to keep their metabolism revved up. However, our ancestors in northern Spain lived in an area that didn’t have enough fat-rich food to support them during the cold winter months, making them resort to cave hibernation.

While seasons come and go, winter is often the harshest and most difficult to survive. This season of extreme cold and limited food tests the limits of every animal. It has also created countless biological miracles, from epic migrations to rewiring cellular structures, showcasing how life on this planet can not only adapt to harsh conditions but thrive.